Introduction

Effective care navigation is a key enabler of a modern general practice access model. This guide is for general practice teams who are seeking to improve the care navigation and triage processes in their organisation.

This guidance is based on learning from various practices and primary care networks (PCNs) across the country on how to approach improvements to your care navigation processes. It contains some examples and tips for illustration.

This guidance is 1 of 5 modern general practice ‘how to’ guides. The other 4 guides focus on:

- How to align capacity with demand in general practice

- Creating highly usable and accessible GP websites (includes sections on integrating with the NHS App and encouraging patients to use online channels)

- How to improve telephone journeys in general practice

- How to improve care related processes in general practice

These are all available via the resources page of the national General Practice Improvement Programme.

The national General Practice Improvement Programme (GPIP) provides a range of ‘hands on’ support offers to practices and PCNs to help move to a modern general practice model. Skilled facilitators work with practices and PCNs to help map out their model, to analyse and interpret their own data and to support them with improvements.

Modern general practice and care navigation

The Delivery plan for recovering access to primary care commits to supporting the implementation of a modern general practice model.

Due to increases in the demand for general practice input and the complexity of the presenting workload, a change to the model of general practice is necessary (see figure 1 below).

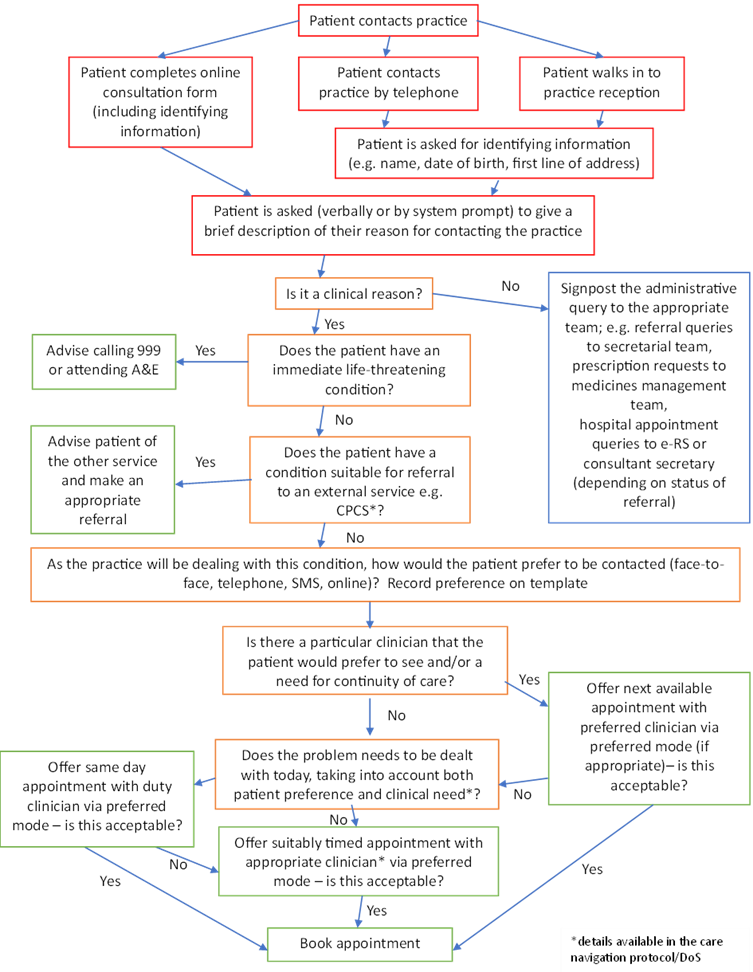

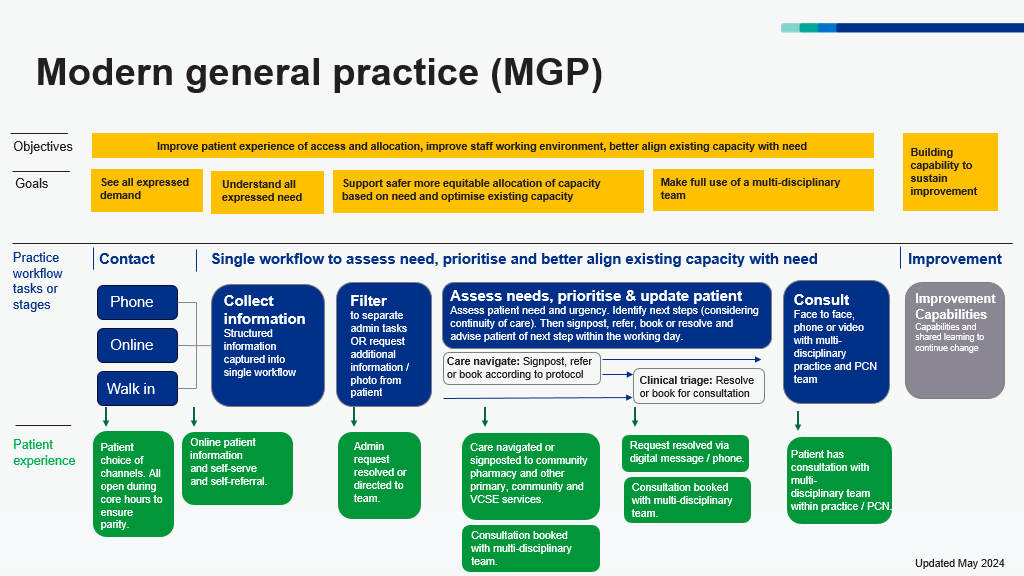

Figure 1: modern general practice model

Figure 1 shows that the overall objectives of the modern general practice model are better alignment of capacity with demand, an improved working environment for staff and improved patient experiences. There are 3 access routes to general practice for patients which are telephone, online and walk in. Information is collected at the point of contact to help care navigate patients to the right service at the right time, based upon need and not first come, first served.

A better understanding of patient needs is required to enable more effective and equitable ways of allocating available capacity including increasing continuity of care where needed.

A wider range of roles and services make up that available capacity, and care can be delivered by a wider range of consultation modes.

Collecting structured information at the point of contact (regardless of the access route) enables us to use this information to:

- inform filtering of clinical and administrative queries

- navigate requests to the right service or member of the team

- prioritise requests and allocate to the right appointment type (timeframe, healthcare professional and modality) to meet the need.

These are key steps to a safer, more equitable and more sustainable model of general practice. This guidance will help practices and PCNs implement and optimise these steps.

Much of this will be new to patients and it is vital to improve patient understanding through meaningful communication.

Benefits of effective care navigation

Effective care navigation could direct over 15% of patient contacts to teams that could better help them: administrative teams, self-care, community pharmacy or another local service. Other patients can be directed to the most appropriate practice staff member for assessment and response, without first being seen by a GP.

Effective care navigation and triage help practices understand the nature and urgency of requests for help from patients and to navigate these requests to an appropriate service or healthcare professional within an appropriate timeframe and supports patients to find the best solution for their needs.

For patients, effective care navigation can:

- prioritise care based on need, providing safer and more equitable care

- access care from the right healthcare professional in the right way first time

- increase appointment availability throughout the day

- enhance relationships with the practice, improving continuity of care where needed and reducing complaints

- empower patients to use self-serve and self-referral services where appropriate and available, for example by ordering repeat prescriptions online or self-referring to antenatal services

- create a more transparent process and better-informed patient cohort, enabling more personalised care and better-informed choices.

For practices, good care navigation can:

- reduce potentially avoidable appointments within the practice, freeing up clinical resource

- make best use of the multiprofessional team and multi-agency support in the community

- improve continuity of care for those that need it through a risk stratification approach to prioritise continuity of care needs

- improve efficiency and reduce failure demand (avoiding duplication and decreasing avoidable work)

- allocate appointments fairly across staff

- improve patient and carer experience

- improve staff experience and wellbeing

- reduce unnecessary A&E attendance

- encourage integration of health, social and voluntary sector services.

Section 1: 4 steps to create and implement care navigation

Successful care navigation requires careful consideration and planning. The 4 steps below guide you through a process to implement a care navigation process.

1. Understand

- demand and capacity

- avoidable appointments

- key measures

- starting point.

2. Design

- care navigation flow

- care navigation protocol

- create directory of services

- training.

3. Go-live

- structured information gathering

- re-design of appointment book

- digitally enhanced process

- testing/implementation plan

- communications strategy.

4. Measure and improve

- evaluating success

- sustainability planning

- automation.

Step 1: understand

To help organise your thinking, a practice should:

- Measure and analyse demand and capacity data to obtain baseline data. For more information on how to do this there is separate guidance and webinars on how to align capacity with demand’ available via the national General Practice Improvement Programme resources section.

- Undertake an avoidable appointment audit to identify how many appointments could potentially be navigated elsewhere. This can also give an understanding of the number of appointments requiring continuity of care. This is explained in separate guidance ‘How to align capacity with demand’ available via the national General Practice Improvement Programme resources section.

- Using data gathered in 1. and 2., you will need to decide on key metrics or measures that will help you demonstrate any improvements you make to your care navigation process. The section entitled ‘Putting measurement in place in step 2 (part of step 2: design)will help with this.

Practice leadership should then discuss the data and analysis and agree to implement or enhance the practice care navigation process.

It is important to secure buy-in across the whole clinical leadership team. Identification of a clinical champion is recommended.

Hold a whole practice meeting to agree the approach to embedding care navigation, this must include both administrative and clinical team members.

Top tip

If call wait times are long, causing poor patient satisfaction and additional stress on reception teams, it may be best to tackle call wait times initially to make it easier to ‘go live’ with care navigation. Be prepared that, especially at the start of implementation, there may be an increase in call length and therefore call wait times.

See companion guidance “How to align capacity with demand” and “How to improve telephone journeys” available via the national General Practice Improvement Programme resources section.

Top tip

To make things easy to begin with, use your baseline data to identify your 5 key presentations that could be dealt with differently in-house. Focus on these when formulating your protocols and directory of service (eg referral to Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme roles or specific roles within practice).

Once you have developed a process for putting this together, adding further presentations will become easier to do and you can expand your protocol and directory of service accordingly.

Step 2: design

An effective care navigation process should be consistently applied. It should start from the first contact of the day and requests managed through a single workflow.

This enables the system to be equitable and based on clinical need no matter which mode of access is chosen by the patient or the time of day the patient makes contact.

It should also be recorded. Every contact’s outcome should be recorded in the clinical notes for training, monitoring and safety purposes. Structured information can be collected over the telephone or in person and captured in a digital template, or by the patient completing an online form to create a digital record.

Care navigation models have 3 key elements:

- A structured approach to collecting information from patients through all modes of contact.

- A protocol to support practice staff in navigating patients confidently and consistently to the right service or healthcare professional within the appropriate time.

- A directory of services providing care navigators with up-to-date information about the services patients can be navigated to.

It is recommended that a practice develops a map of their proposed care navigation process. Consideration must be given to managing service propriety, urgency, and continuity.

An example map is included below in figure 2.

Figure 2: example care navigation process map

Figure 2 (a flow chart) is an example of a care navigation process which maps the steps from point of contact, through care navigation based on patient need, onto appropriate outcomes which may include a general practice appointment or signposting to another service that can better meet the patient’s needs.

Collecting structured information from patients

This is an important step to enable filtering, navigation and prioritisation of requests based on need. It increases the ability to close encounters with a message or allocate the right consultation modality first time and allows clinicians to be ready with the right results or information for patients at the point of consultation.

Structured information can be collected over the telephone or in person and captured in a digital template, or by the patient completing an online form.

This information should include:

- patient’s age, sex (and who is completing the form, for example carer)

- what’s the problem? What are the symptoms?

- is this a new problem or an existing issue? How long have you had this?

- is it getting worse, stayed the same or getting better?

- have you tried anything for this?

- have you seen anyone about this?

- what are your expectations?

- would you prefer a consultation by phone, face-to-face, video or message?

- would you prefer to receive help from a specific healthcare professional? If so, who?

- when are you not available?

- do you have any specific communication needs? For example, interpreter required

- confirm the telephone number and if consent has been given to use SMS communication if needed.

For some specific presentations, further information may be usefully gathered to support later clinical assessment. This information can be requested/received via standardised forms (eg suspected urinary tract infections), photographs or by ordering appropriate tests prior to clinical review. This reduces the number of contacts a patient requires to reach resolution of their query.

Top tips

- Remember to code communication needs and a patient’s SMS communication preferences in the patient’s clinical record.

- Make every contact count; use online forms to request information to support a long-term condition and/or medication review opportunistically which will simultaneously support the practice achieve their quality targets (eg Quality and outcomes framework) spread throughout the year.

- Access to telephone headsets and dual screens for care navigators are very helpful in supporting staff with this process.

- A headset with a specific noise reducing microphone helps to cancel out any background noise for the patient and member of staff. You may need to check your phone has a USB port to connect the headset to.

Creating a care navigation protocol

The care navigation process should be supported by creation of a written care navigation protocol. This is used to filter patients and direct them to internal (practice and primary care network based) healthcare professionals and external resources where appropriate.

Staff will need training and support to understand the scope and use of new roles to ensure optimum take-up. A skills matrix can be used to support this, an example of which is available as a spreadsheet to download from the national General Practice Improvement Programme resources page

As a minimum, this protocol should include:

- common clinical and administrative requests

- instructions for patients with specific needs, eg vulnerable patients, disability, young children, frail complex patients, specific communication needs, patients who frequently present

- navigation to self-serve options, eg online repeat prescription ordering

- navigation to services within general practice, additional roles in practice or primary care network

- navigation to a service outside of general practice, eg community pharmacy, sexual health services

- who to approach for support

- what to do when the appointment book is full.

For clinical requests, the protocol should include:

- inclusions/exclusions for the presenting condition

- urgency of appointment recommended (eg same day, this week, within 2 weeks)

- most appropriate mode of appointment (face to face or remote)

- duration of appointment required

- any specific requirements for that appointment (eg before 2pm if phlebotomy, patient to bring inhalers with them if attending an asthma check, interpreter needed)

- most appropriate clinician (can be by role, eg GP, practice nurse, health care assistant, primary care network access hub or a named clinician depending on the skill mix within the practice or if patient has requested a female or male clinician)

- identify continuity of care needs and with whom (eg patient’s usual clinician, the clinician consulted in the last 6 months, clinician that ordered the test, patient’s preferred clinician).

A key rule is that all clinical requests not allocated by care navigation need to come into a single flow for assessment.

Administrative requests: have a clear distribution route within practice and agreed turnaround times, eg 7 days for fit notes, 2 weeks for insurance reports.

Management of overflow demand: whilst demand is predictable, at times there may well be surges of demand that outstrip available capacity. It is important that care navigation teams have clear processes to follow when this happens, and these are clearly documented. For example, being able to book additional slots across all clinical team members, adding to a separate list for triaging, agreed use of primary care network wide services.

You might want to use the care navigation protocol template below as a basis to build your own protocol.

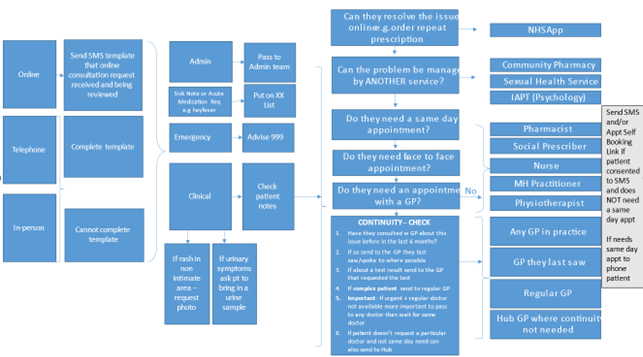

Figure 3: care navigation protocol template

This example care navigation process (figure 3) outlines the different access routes, types of queries that can be received and maps them to the most appropriate teams and professionals.

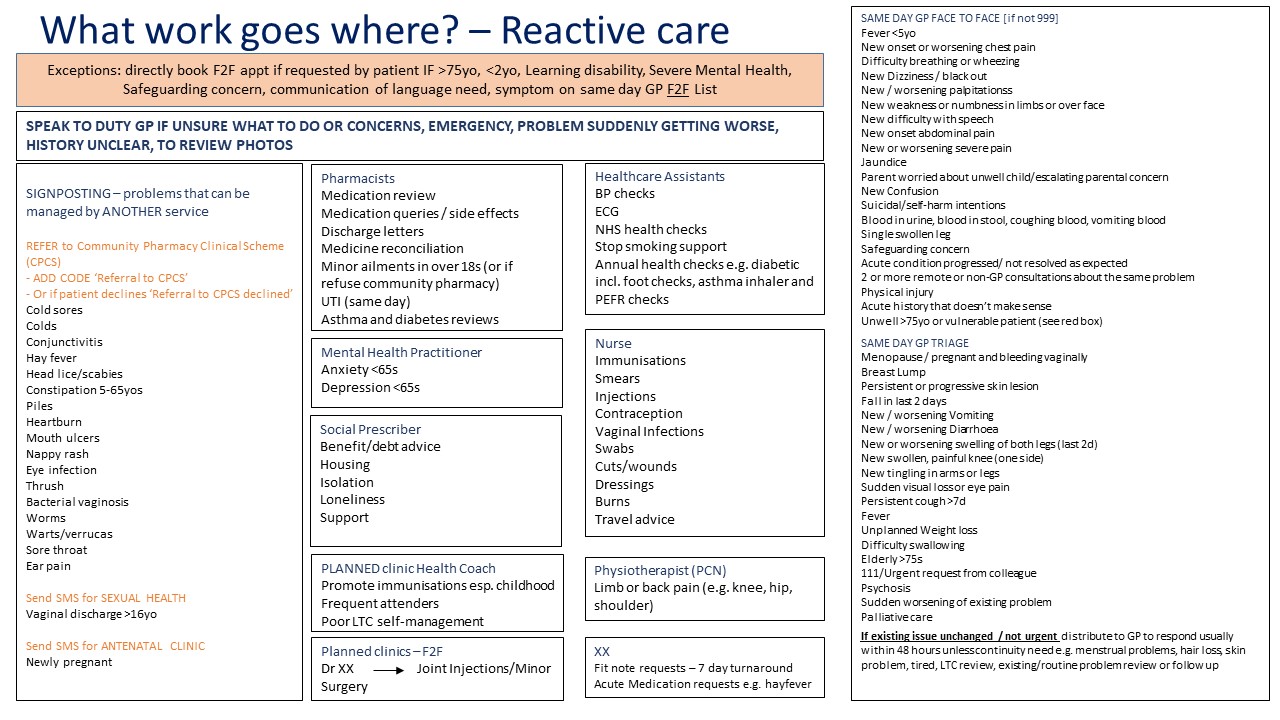

Figure 4: example practice care navigation templates

This template (Figure 4) supports care navigation and outlines a range of professionals and services patients can access, along with the type of support/expertise they can provide.

Top tip

Consider testing your care navigation protocol initially with some of your staff to see whether all the necessary information is covered and where there may be gaps. In addition, you may want to consider how you will ensure that there is ongoing learning and development of the protocol once it is in active use.

Top tip

When starting to use your care navigation protocol, consider having your most skilled and experienced care navigator ‘floating’ amongst the team to support them and answer any queries that arise. For some practices this might be a GP, for others it might be the practice manager, a care coordinator or care navigation champion. Print off a copy of the protocol and save in a shared folder so staff can access it quickly.

Formulating a directory of services

For external services, it is recommended that a directory of services is compiled. This should include additional information including a brief descriptor for the service, its location, opening times, contact details, and how referrals should be made (eg self-referral, completion of form/template by practice, by phone).

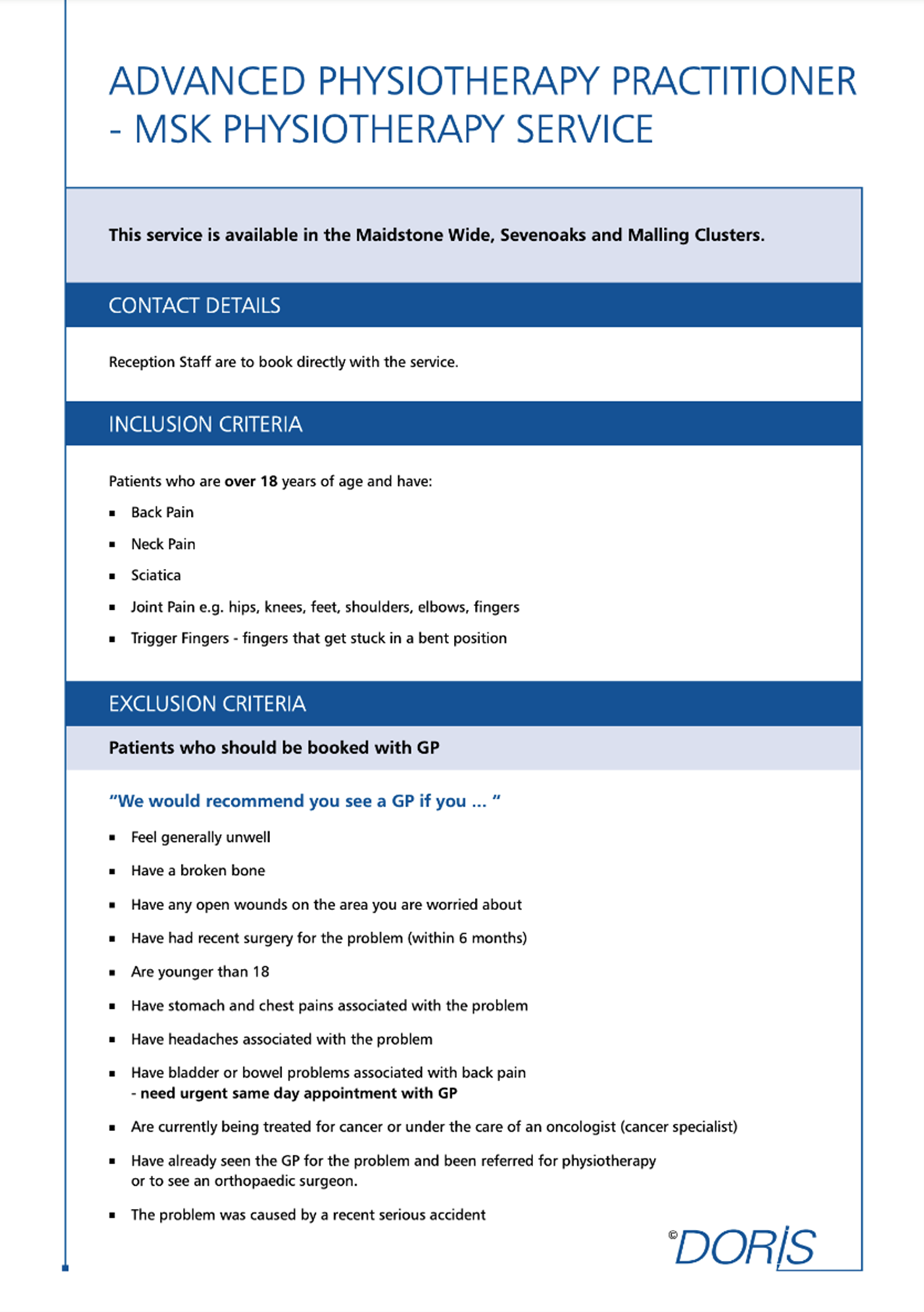

A sample of a page from a directory of service is shown below (courtesy of West Kent), you can see further pages in the appendices.

Figure 5: sample page from a directory of services

Figure 5 is an example of a directory of service entry which outlines which patients and conditions are suitable to be referred to or signposted to an advanced physiotherapy practitioner who can support with particular patient needs.

Top tip

To save time across individual practices, consider the creation and maintenance of a directory of service at primary care network, neighbourhood or locality level.

External services can include secondary, tertiary and community health services, other statutory services, eg social care, other commissioned services, eg drug and alcohol teams, public health services (such as weight management, sexual health, Department for Work and Pensions, housing), community and voluntary sector, eg food banks, Citizens Advice Bureau, parenting (HomeStart), and many other local voluntary, community, faith, and social enterprise finally businesses (a potential resource which may require closer consideration). Getting to know these providers, building relationships with them and understanding the scope and ethos of their service can not only enhance your care navigation success but also lay strong foundations for future integrated neighbourhood working.

Top tip

Your social prescribing link workers, health and wellbeing teams and/or county council may already hold a comprehensive directory of services so check with them first to avoid reinventing the wheel.

Aligning your appointment book, rota and care navigation model

A structured appointment book helps to give clarity but should also offer flexibility in response to the demands of the day, offering contact types to meet individual patient circumstances and needs. Carving out inflexible times for each appointment type risks wasting valuable capacity and contributes to clinician stress.

Guidance on how to redesign your appointment book and rota to align with your care navigation model can be found in the companion guidance document How to align capacity with demand via the resources section of the national General Practice Improvement Programme.

Top tips

- turn off automatic SMS reminders to patients for triage slots

- align appointment book slots with associated GP appointment data categories

- align Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme smartcards

- agree how you will view and manage your clinical workflow, eg within your online consultation system or using the clinical system.

Staff training in care navigation

Any staff member can be trained to undertake care navigation, irrespective of role.

Many practices will use administrative or reception staff roles to fulfil this function, others may have a specific patient liaison or care co-ordinator team. Clinicians are also able to follow this process. Whichever route you decide works best in your practice, the aim is to achieve consistency in experience for the patient, irrespective of who handles their enquiry.

Training your staff to deliver your care navigation process should include, not only an understanding of the details of the process, but also guidance on how it should be delivered.

Strengthening your team’s customer service skills will be of great benefit. Careful listening, demonstrating empathy and patience, being adaptable yet consistent, sharing knowledge in a way that allows the patient to feel able to make an informed choice, and all whilst maintaining personal resilience are important attributes that will require training and practice to perfect.

The care navigation process should ensure that there are clear lines of immediate clinical support for staff when queries arise, as well as ongoing opportunities for learning and development.

National care navigation training: NHS England has rolled out a new national care navigation training programme for up to 6500 staff. This aims to develop knowledge, understanding and confidence in care navigation.

Objectives:

- Enable participants to understand the purpose of care navigation and the impact it can have in improving population health.

- Define the role and boundaries of care navigation.

- Develop understanding of the wider determinants of health and importance of making every contact count.

- Support participants to understand the purpose of the local directory of service and useful local partner organisations.

- Build confidence in signposting patients to local services.

For further information please email carenavigationtraining@england.nhs.uk.

Top tip

Consider identifying a primary care network level care navigation champion and trainer.

Tips for communicating well

Good communication between the GP practice team and the patient are key to effective care navigation.

Many practices provide regular training and support to first contact staff. Practices in research have shared the following tips and phrases staff find useful when speaking with patients:

At the start of a conversation:

- Use open questions (eg why? how? what?) to allow patients to share information in their own words, encourage conversation and promote engagement.

- Make a positive exploration with the patient into the circumstances of their query. This will promote more confidence, less frustration and lead to a better dialogue enabling more effective navigation.

- “If you can tell us a little more about your enquiry, we can direct you to the right person/identify the best source of help for you – would you mind sharing some information with us please? This information is entirely confidential”.

- “Have you already seen a member of our practice team about this issue?”.

- Refer to the patient’s contact as a query or enquiry, rather than a call or a reason.

- Use ‘we’ and ‘us’ to promote consistency of your practice team message.

- “Our staff are using a procedure that has been designed and agreed by the GPs”.

- “If we don’t have any information, the doctor can’t prioritise your case…”.

- “I understand you may feel uncomfortable telling me, to reassure you it’s entirely confidential, and if you prefer you can complete the form yourself by going online….”.

- Be clear what happens with the information “the information will be passed directly to the doctor”.

- “Dr xx has asked me to help you as (s)he doesn’t want you waiting unnecessarily to see/speak with someone …”.

- “The practice is trying out a new way of taking calls so may I try and help you now and you are most welcome to give your feedback to the GP when you next see them”.

- “The reason we can’t do that is…..”.

- “I’m sorry we didn’t do that….”.

- “Thank you for your help”.

Towards the end of a conversation:

- “Do you have any questions or concerns about the information and options we have shared with you today?”.

- Use a reassurance message at the end of each conversation, irrespective of access route (eg “Please come back to us if you have any questions or concerns”). This helps build the patient’s confidence and increase their understanding of how navigation can work effectively for them.

Avoid phrases such as ‘we are experiencing high demand’ as they can create negativity and frustration for patients, potentially leading to conflict between patients and staff members.

Putting measurement in place

Measuring from the beginning of implementation of care navigation is important to understand where it is working and where ongoing improvements need to be made. There are a range of measures that can be used, some examples of which are the:

- number/an audit of potentially avoidable appointments

- number of referrals to community pharmacy consultation service (CPCS)

- number of recommended referrals to CPCS declined by the patient

- number of referrals to social prescribing link worker

- number of appointments sign-posted to non-GP/wider multidisciplinary team

- number of reattendances within 2 weeks for the same issue

- number of patient complaints about ability to see a GP

- percentage of patients not receiving continuity of care where it is needed.

Step 3: Go live

Creating and testing the implementation plan

There are multiple steps involved in setting up your care navigation process, as outlined in this guidance, and you will have additional ideas of your own.

Evidence tells us that following quality improvement methodology, and testing each element to ensure it is working in the best way possible for you, is highly beneficial in achieving your desired outcomes.

Draw up a programme of testing that is appropriate for your practice. A suggested path might be as follows:

1. Start with some quick wins such as:

- changing the telephone message

- creating a skills matrix (who can do what) for your internal and Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme staff, an example of which is available as a spreadsheet to download from the national General Practice Improvement Programme resources page

- training care navigators and receptionists on scripts and to use them consistently. Print these off so staff have them to hand

- navigation of high-volume requests that do not require general practice, eg referring minor ailments to CPCS and/or start with the most common presentations identified by your avoidable appointment audit

- use of cloud-based telephony call-back functions to avoid patients waiting on the phone and call routing functions to enhance care navigation.

2. Build on this by training your identified care navigation staff and creating a care navigation protocol that you test and refine until it is working well.

3. Create a directory of services at primary care network level and test this (to check content, format and accessibility) until you reach a point that is acceptable for you and your patients.

4. Align your appointment book and rota with your care navigation model.

5. Use digital tools (online consultation tools, appointment booking links, pre-set templates in your messaging tool) to capture structured information from patients at the point of contact to make care navigation and appointments more effective. Use this to also quickly send information and links to patients about specific services, service finders or to offer self-booking links into an appropriate appointment. Have the phone numbers for your supplier and local IT support to hand when going-live.

6. Confirm the go live date and work towards it. When moving to a new operating system it can be helpful to clear the appointment book. Practices have found it helpful to have extra clinical cover leading up to or for the first few weeks of ‘going live’ to have additional capacity to ‘work off’ the backlog. Practices can access transition cover and transformation support funding via their integrated care board to help support this. Avoid launching a new system on a Monday or Friday and ideally launch when you are expecting to have a full team.

All the time you are undertaking your improvements, measure your key data and track your progress. Recording your progress is essential to understand the improvements you’ve made.

The national General Practice Improvement Programme webpages, contain more information on quality improvement methodology.

Communicating changes to patients

Engaging your patients in this new way of working is key to its success.

It is important to keep them informed as a minimum requirement. Consider the following steps in your engagement strategy:

Recommended:

- Record an informative message on your telephone system about care navigation. For example, explaining why we might ask for a little more information. Using your GPs to do this can be particularly impactful.

- Use your text messaging service to inform patients of the new service/way of working.

- Describe your care navigation process clearly on your website. This webpage courtesy of Witton Medical Centre in Blackburn describes their care navigation process.

Could also include:

- Create posters for the practice featuring your GPs.

- Mailshot local schools, other health and care providers, etc. using your GP posters.

- Create social media and short explainer videos.

- Press releases to local media providers.

To make your care navigation process as user friendly as possible, involving patients in the design and creation of the communications is recommended.

In addition to offering the user perspective, your patients can help you with crafting approaches that are clear and use appropriate non-jargon language. This can appear daunting but adding this element into your process will reap rewards down the line, particularly in terms of sustainability of your service.

The guide, ‘Using experience based design to improve your service’ provides useful information on involving patients in design.

Top tip

For message recording:

- Select a member of the practice team who is confident in recording messages, potentially a clinician who is well known by patients.

- Remember to reinforce the message of ‘our team’ as this promotes confidence in patients and reduces potential for conflict.

- Ensure the messaging and language used in the answerphone message matches all other communications, eg external communications, waiting room posters, website etc.

Top tip

Many of the new cloud-based telephony systems have auto voices, both male and female. Type in the text you want to be heard and the auto voice will read it out. Changing the voice periodically maintains interest for the patient when hearing the message.

Incremental improvement or big bang?

There is no right or wrong answer to this question, it will be down to practice preference and what feels doable. You might prefer to start with the most common presentations identified by your avoidable appointment audit and develop your process, protocol and directory of services based solely on these, building your care navigator scripts alongside this with learning from testing. You might prefer to build a comprehensive package and launch it in one go. It may depend on how you are approaching the redesign of your appointment book based on your demand and capacity data (see companion guidance ‘How to align capacity with demand’ available via the resources page of the national General Practice Improvement Programme).

Supporting staff when you go live: as with any change process, it is essential that staff taking on new responsibilities receive adequate support. This is particularly important during the early stages of implementation.

How this support is approached will vary depending both on the speed of launch and individual practice factors but may include:

- daily huddles

- regular clinical meetings

- experienced floor walker on “go live” day

- named clinician for immediate support

- whiteboards to gather less urgent queries with dedicated time to review and respond

- structured approach to reviewing recorded episodes for training and monitoring

- build in safety checks – is the protocol/model doing what it’s supposed to do

- peer to peer support, eg through teams chat and/or care navigation champions

It is important you have consistency of practice across all clinicians regarding approach, speed and effectiveness.

Top tip

An external facilitator, for example via the intermediate and intensive national general practice improvement programme support offers, can be very helpful in reviewing variation in practice amongst the team as it can be difficult to achieve the degree of openness required whilst remaining neutral.

Step 4: Measure and improve

Evaluating success

All improvement work should be data driven. Give some thought to how you will evaluate the success of your changes. This has already been discussed earlier in the guidance and sample measures were suggested in the previous section entitled Putting measures in place (part of step 2: design).

It is important to set a clear aim and outline the expected outcomes you might see as a result of implementing or enhancing care navigation in your practice.

Outcomes you might seek are:

- reduction in avoidable appointments with the practice and with GPs

- improvements in continuity of care

- reduction in complaints

- improvement in staff wellbeing – sickness, burnout, joy at work

- reduction in call waits by reducing overall telephone demand through increasing use of self-referral and self-service options

- increased use of community pharmacy clinical services

- improvement in Friends and Family Test or other local patient experience measure.

Any activity should seek to serve whatever outcomes you have set.

Sustainability planning

Once you have successfully implemented your care navigation process and it is working well, give some thought to how you will maintain the gains you have made, and whether they could be further enhanced. For example, adding digital solutions can certainly make the process easier. Expanding the success across your primary care network (PCN) or locality can also be of benefit, sharing protocols and using a unified directory of services maintained at PCN level is a time saver for each individual practice, perhaps even a unified telephony and triage hub may be something of interest.

Trouble-shooting problems as they arise and risk assessing your process in order to mitigate potential problems is a useful activity. For example:

- How will we manage ‘extras’ once we have run out of appointments?

- How will we deal with errors (patient is recommended to an inappropriate service)? How will we deal with complaints/disgruntled patients?

- Do you have good processes and digital tools by which you can ensure enough information is collected from patients, eg phone scripts and key questions to support staff, online or messaging templates for asking for additional information (photos, questionnaires), making sure all the information/tasks are done before booking an appointment?

You will need to have a plan and allow time for ongoing training and mentoring for staff, keeping your protocol and directory of service up to date, ongoing patient communications activity and continuous monitoring of your measures over time. All this will enable you to ensure that your progress is maintained.

Section 2: Digital tools to support care navigation

There are a range of digital tools that can support and enhance care navigation

- Cloud-based telephony

- online consultation tools

- messaging tools

- tools which generate self-booking links allowing patients to choose and book an appropriate appointment.

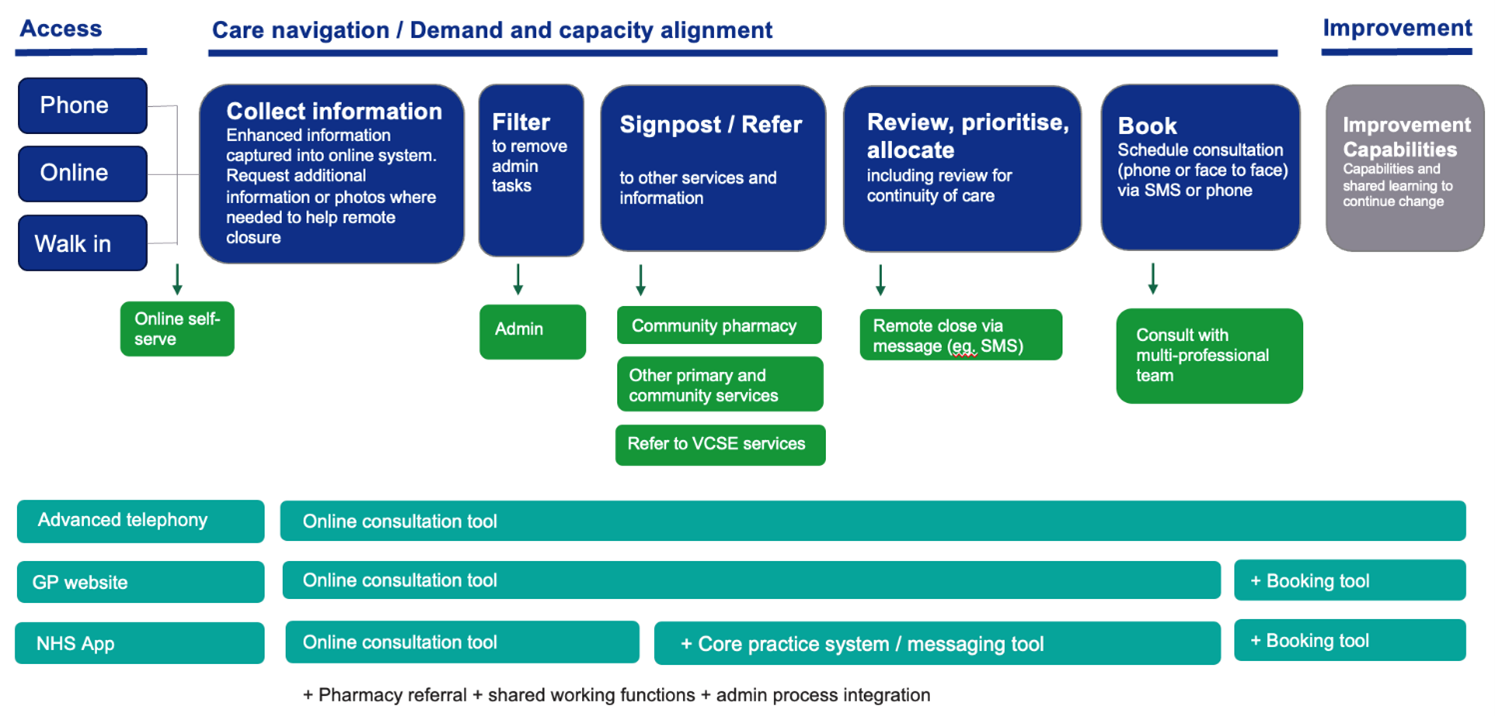

Figure 6: the range of digital tools that support the different elements of the modern general practice model

Figure 6 shows that the overall objectives of the modern general practice model are better alignment of capacity with demand, an improved working environment for staff and improved patient experiences. There are 3 access routes to general practice for patients which are telephone, online and walk in. Information is collected at the point of contact to help care navigate patients to the right service at the right time, based upon need and not first come, first served.

A new digital care services framework will be released at the end of August 2023 which brings together online consultation, messaging and appointment booking tools into a single purchasing framework to help integrated care boards purchase assured digital tools on behalf of their primary care networks and practices.

Cloud-based telephony

The analogue phone network will be switched off in 2025, which means all practices will need to move to cloud based telephony.

This advanced telephony provides many additional features and benefits such as call back and call routing functions to support care navigation and make data easily accessible to practices.

You can find full information in companion guidance ‘How to improve telephone journeys in general practice’ available via the resources section of the national General Practice Improvement Programme.

Online consultation tools

Online consultation tools provide:

- patients with a means of requesting clinical and administrative help from their practice

- practice staff with a range of functionality to receive, review, prioritise, allocate, action and keep a record of requests from patients.

Online consultation tools are an important part of the workflow of general practice admin and clinical teams. These tools:

- provide patients with equitable access and choice of contact channels; enabling patients to choose channels and times to contact GP surgeries that suit their needs

- support practice staff to collect structured information about patients’ clinical needs; to support better assessment of need and urgency which facilitates allocation of clinical resources

- support care navigation processes; by providing tools and functions to review, assess, prioritise and allocate patient requests to teams, roles and individuals at different stages of care navigation, triage and booking

- support effective and equitable allocation of clinical skills and time; to match patient need to the appropriate clinician, within the right time frame, using an appropriate consultation modality (written, phone, video, face to face)

- reduce practice burden; by increasing workflow efficiency and releasing time for general practice staff.

To make online consultation forms a usable and desirable channel for patients 7 key needs were identified from extensive user research and user testing with patients and general practice staff from across England:

Online consultation forms need to be:

- Straightforward to access; in my preferred channel (web, app etc).

- Straightforward to find and start; clearly labelled and ideally without the need to register or login.

- Straightforward to understand what is required of me; no more reading than necessary, using written content that meets NHS guidance.

- Straightforward to complete; no more reading than necessary and I can express all my needs easily and clearly.

- Provide clear expectation setting; I understand what will happen with this information and when and how I will receive a response.

- Be highly accessible; my end-to-end journey is fully accessible.

- Be highly usable; journeys consistent with NHS design standards.

Patients often use the phone to contact their GP surgery rather than using online channels because:

- it’s a familiar channel

- they are not aware they can do key tasks online

- they are not aware of any benefit in doing these tasks online

- the online journey is poor or hard to understand and complete

- they are left unsure about next steps.

To make an informed choice about the contact channel patients need to know:

- the benefit to them

- in what timeframe their request will be assessed

- how and when they will receive a response

- that the urgency of acknowledgement and initial assessment via this channel matches the urgency of their need.

We recommend practices:

- tell patients about the benefits to them

- communicate in an appropriate and most direct channel with clear actions for patients to act on, eg ‘request an appointment online’

- be clear if different response times are applicable to administrative and clinical requests

- be clear about when a member of the GP surgery will read and review clinical requests

- communicate how they will make contact with the patient

- communicate when the practice is open and what the patient should do out of hours or if the matter becomes urgent or an emergency.

Having consistency of message across the channels in a practice is key to success.

Ensuring each relevant channel is used to promote the strategy will support the messages to patients. Most practices have:

- verbal touchpoints – staff

- text (SMS) and email

- website

- physical touchpoint – practice posters and screens, leaflets

NHS England provides a written content template for ‘appointments’ webpages for the practice website. This written content meets the patient needs above and has been tested with patients for clarity and meets the NHS recommended reading age.

Expectation setting information should be provided at the start of an online consultation form and on submission/in the confirmation screen.

Many practices described in research some of the ways in which they are supporting patients to go online in their practice, including:

- working in partnership with patient liaison teams and local voluntary sector organisation to support patients in going online

- running drop-in sessions or spending time in the waiting area to support and encourage patients to get set up with accounts.

- identified digital champions in the practice teams

- identified NHS App ambassadors in the practice teams.

Our research showed people are not familiar with “online consultation”. When the term is used for an online form it’s misleading. Many people think it means they’ll have a consultation with a doctor online, rather than complete a form to request an appointment.

If you are talking about a phone, video or face-to-face consultation with a doctor or other health professional, be clear about the format.

NHS content style guide entry on online consultation

Online consultation

Do not use the term “online consultation” or any variation of it, like “eConsultation”.

If you’re writing about using an online form to contact a GP surgery, be clear about the task and the outcome.

The best way to describe this may depend on the context and the service that’s available.

For example, you could use phrases like:

“Contact your GP using an online form”.

“Request an appointment (online)” where this is relevant, for example on a GP surgery website alongside offline booking options.

Choosing an assured well suited online consultation tool can bring benefits to both patients and general practice staff:

Patients are able to:

- request help without waiting on the phone

- do administrative tasks at a time of the day to suit them

- take their time to explain their needs in writing rather than feeling rushed and flustered in a short call

- share sensitive information with the GP surgery without having to explain it to over the phone to someone unfamiliar

- share information they wouldn’t be able to share over the phone (for example sending a picture of a rash).

For practices it:

- can reduce the 8am rush by moving telephone demand to an online channel

- give a full view of demand and detail; helps allocate capacity effectively

- give a full view of demand and detail; helps navigate to other services and relieve pressure on practice appointment capacity

- provides the ability to review and remote close patient requests

- provides data to help understand demand and capacity and support planning.

Messaging/messaging and booking tools

Messaging tools provide important functions to support care navigation workflows to:

- ask for further information from a patient to understand need

- request further actions from the patient ahead of a consultation to make best use of the consultation for the patient and healthcare professional.

- receive that information from a patient and to code and record that information to the patient record. For example, for Quality and outcomes framework activity and flu vaccinations

- send a patient a self-booking link for an appropriate appointment

- send reminders about appointments

- send alerts, for example 15 minutes before a clinician calls

- send follow up information after a consultation

- manage specific administrative requests, eg fit notes.

We recommend creating shared messaging templates for common processes, these can often be created and shared throughout a primary care network.

Some of these functions described above can be provided as part of an online consultation tool and sometimes within a separate messaging (and booking) tool.

We recommend mapping out the steps in practices process to check the functions that are needed and then checking the functions of the online consultation tool or messaging tools to see if they meet your requirements.

When implementing a digital system, review information and clinical governance requirements:

- update your data protection impact assessment and privacy policy. You can find clinical safety information and governance templates on Future NHS (requires registration)

- work with your integrated care board (ICB) to mitigate clinical safety risks. A clinical safety risk assessment DCB0160 should be carried out by the ICB on behalf of their practices, with individual practices working. collaboratively with the local clinical safety officer. You can find clinical safety information and governance templates on Future NHS (requires registration)

- patients need to know if decision-making is being automated (where a person is not involved in the process) and agree to it – they must have the option to have the decision reviewed manually

- update your safeguarding and chaperone policies to include remote consultations

- ensure all staff know how to identify and escalate incidents and concerns. Adapt existing processes for recognising, analysing and learning from incidents.

Staff Training

Suppliers will provide training to all staff on deploying and using the software. They will explain the process for reporting incidents or issues and provide you with a point of contact. It is important to:

- ensure staff are aware of how and where they can access resources: eg guidelines, protocols, IT support, supplier contacts

- ensure everyone is clear about their roles and responsibilities, and specifically acknowledge the new role for reception staff

- ask about digital literacy, training and development needs

- provide team and peer-led training (confident users support others) and a go-to person for support/queries

- use ‘test patients’ and team simulations to get familiar with the system and check IT/logins are working

- encourage staff to submit their own test online consultation requests to see how it works from the patients’ perspective.

Appendix 1: example telephone messages/call scripts

Example 1

“Welcome to Anytown Medical Centre

“If you have a medical emergency, or a life-threatening infection – please hang up immediately and dial 999.

“Our practice team will work with you to offer you assistance with your query by offering you a range of options, we have a team of professionals working in the practice who are trained to support you. In order to do this, our trained reception [insert and utilise your reception team title as relevant, eg patient advisors] will ask you for some information. This information will help us to understand how to help you as efficiently and quickly as possible, and direct you to the right person to help you.

“Please be assured that all information shared with any member of our practice team remains confidential to the practice.

“If you have access to the internet, you will find online access to the practice services via our website [insert your practice web address] or if you have the NHS app, you will find ways to contact the practice team here”.

Dependant on cloud-based telephony introduction stage for practices, the message should then lead into either:

“Please listen to the following options and make a selection from the options”.

or

“Please wait for the next available member of our team to take your call”.

Example 2

“Hello my name is Dr [insert name] and I am the senior partner at [insert name of surgery] surgery.

You will shortly be put through to our reception staff. We have asked them to ask you if you wouldn’t mind telling them a little about the problem you are calling about today. This is simply so they can direct you to the person who would be most suitable to help you with your problem.

Of course, you don’t have to do this, but it would help us to help you and ensure you see the right person, first. Thank you very much”.

Example 3

“Good morning or afternoon, [insert name of practice], this is [insert your name] speaking, how can I help?

1. Are you calling on behalf of yourself or someone else? Please can I take your/their details:

- date of birth

- confirm phone number

- check consent to send a text message)

- if a carer, check they have consent from the patient.

2. Can I take a reason for your call to understand how we can best help? Or I need to gather some details form you so we can direct you to the best person in the team for your enquiry .

Ask the questions below in this order to gather more information:

3. What are the symptoms?

4. Is this a new or ongoing problem?

5. How long have they had this for?

6. Have they tried anything for it so far and do they have any specific concerns?

7. Have they contacted another health professional or service already?

8. Has it got worse in the last 48 hours?

9. What are their expectations?

10. Would they prefer a consultation by phone, face to face, video or message?

11. Do they have a preferred clinician? Ensure this is captured, and try to ensure continuity of care where possible, but explain this may not always be possible depending on the urgency and availability.

12. Check if there are certain times when the patient won’t be available, for example, if they are at work, school or college.

13. Do they have any contact or communication preferences or needs (such as a preferred number to call. Do they need a translator or an advocate?). Ensure this is captured.

Please have your phone available and a team will call you back within [insert number of hours]”.

Remember: If urgent, change the slot type to ‘urgent’ and message GPs to alert the team. Take as much information about their symptoms and a correct contact number.

Can the patient wait until their usual GP is in clinic?

- If yes, tell the patient when the GP is in next.

- If no, add the patient to the triage list.

Example 4

Introduction: “Good morning/afternoon [insert name of surgery] Surgery speaking how can I help you today?”.

Triage explanation: “All requests are now triaged, ensuring your issues are dealt with as quickly as possible. To help the GP with this process I’m going to ask you a series of questions and may ask you to send in a picture if appropriate”.

Confirm availability: Before we start, if the GP decides that an urgent face-to-face appointment is appropriate for today, you will be offered an appointment which you will be expected to take. Will you be able to attend?”.

Questions from triage template: Use 8 questions in previous section and any condition specific questions such as: don’t forget to always ask regarding temperature; for babies eating and drinking well, wet/soiled nappies. Duration of symptoms and change in more recent days.

Summarise: “So, from what you have told me, you have [insert description of condition], which started [insert date of onset of symptoms]. You would like to have an appointment/call urgently on [insert phone number] phone number.

“Should the GP need to see you, you are at home and are able to come in at any time? Is that correct?”.

Manage expectations: “I have sent this to the doctor for review. Once your triage notes and if appropriate pictures have been reviewed by the GP, one of my colleagues will be in touch either by phone or text, to advise you of the GP’s decision. This should be within the next [insert number of minutes] minutes”.

Wrap up: “Is there anything else I can help you with today?

“Thanks for your call, take care”.

Appendix 2: example directory of services pages

Figure 7 – an example of a directory of service page for referrals to physiotherapy services

Figure 7 is an example of a directory of service page for referrals to physiotherapy services. It includes inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria and which patients it recommends be booked with a GP.

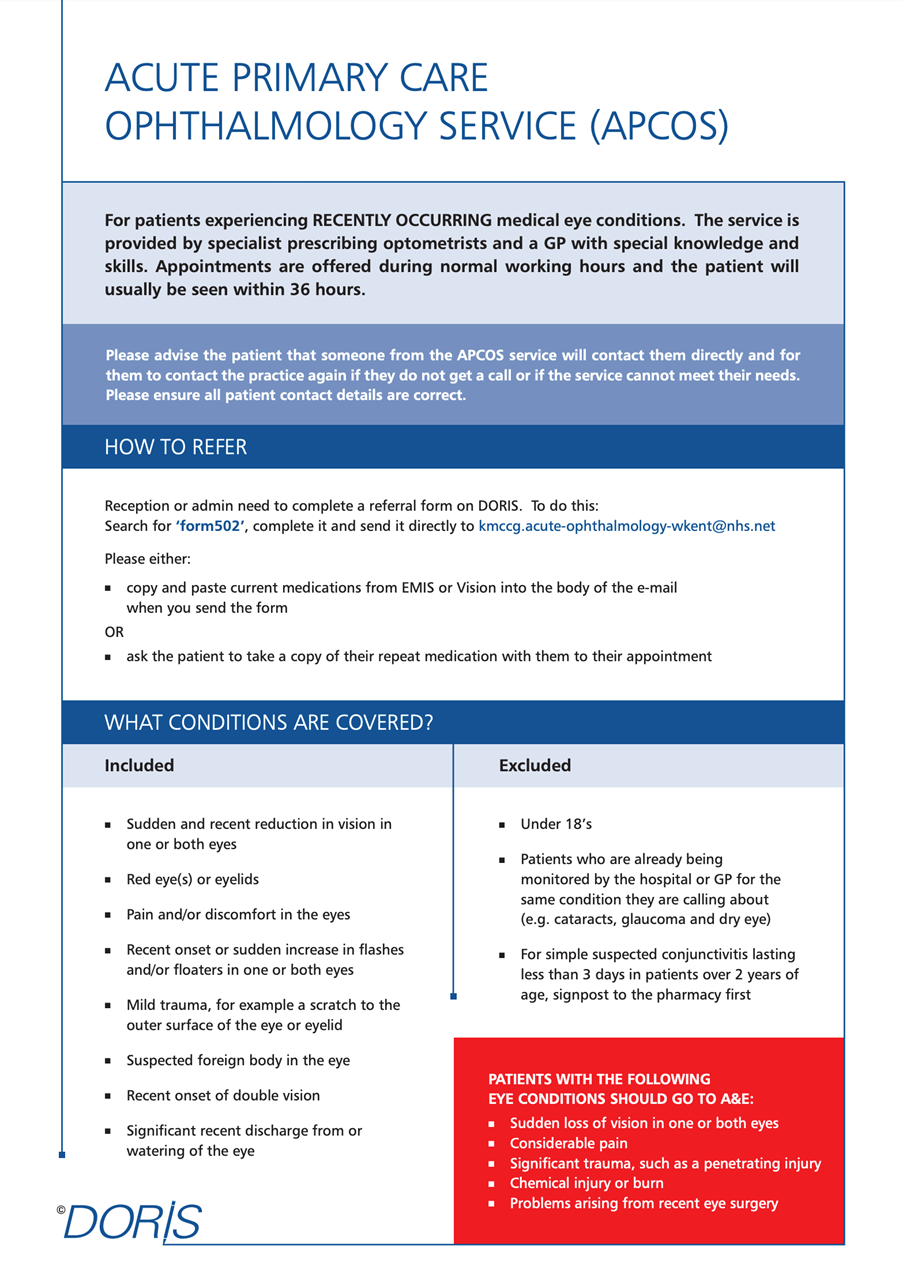

Figure 8 – an example of a directory of service page for referrals to an acute primary care ophthalmology service

Figure 8 is an example of a directory of service page for referrals to an acute primary care ophthalmology service. It includes how to refer and what conditions are covered. It also includes red flags when a patient should be sent to A and E.

How to improve care navigation in general practice

Bakhai M, Vallely D, Fox Z, Joyce J, Cowan D, Carr J, Jacobs E, Mechen C, Shah S, Brand S

This guidance was prepared by NHS England’s Primary Care Transformation team as part of the national General Practice Improvement programme.

If you have any questions or would like to send feedback, please get in touch: england.pctgpip@nhs.net.

Publication reference: PRN00615_ii