Organisation objective

- NHS Mandate from Government

- NHS Long Term Plan

Working with people and communities:

What approaches have been used to ensure people and communities have informed this programme of work?

- consultation/engagement

- qualitative data and insight, for example, national surveys; complaints

- quantitative data and insight, for example national surveys

Work on productivity has been informed by extensive quantitative and qualitative data insight, combining desk-top data analysis and deep-dive qualitative analysis with trusts and systems. Themes from the analysis have been tested extensively with NHS providers and systems, both with leadership and frontline, as well as external stakeholders such as think tanks.

Executive summary

This paper discusses the effect the pandemic has had on NHS productivity with details of NHS England’s estimates for the drivers of the loss of productivity observed. The paper discusses the emerging plan to improve productivity in the coming years.

Action required

The Board is asked to note the information provided in the report.

Background

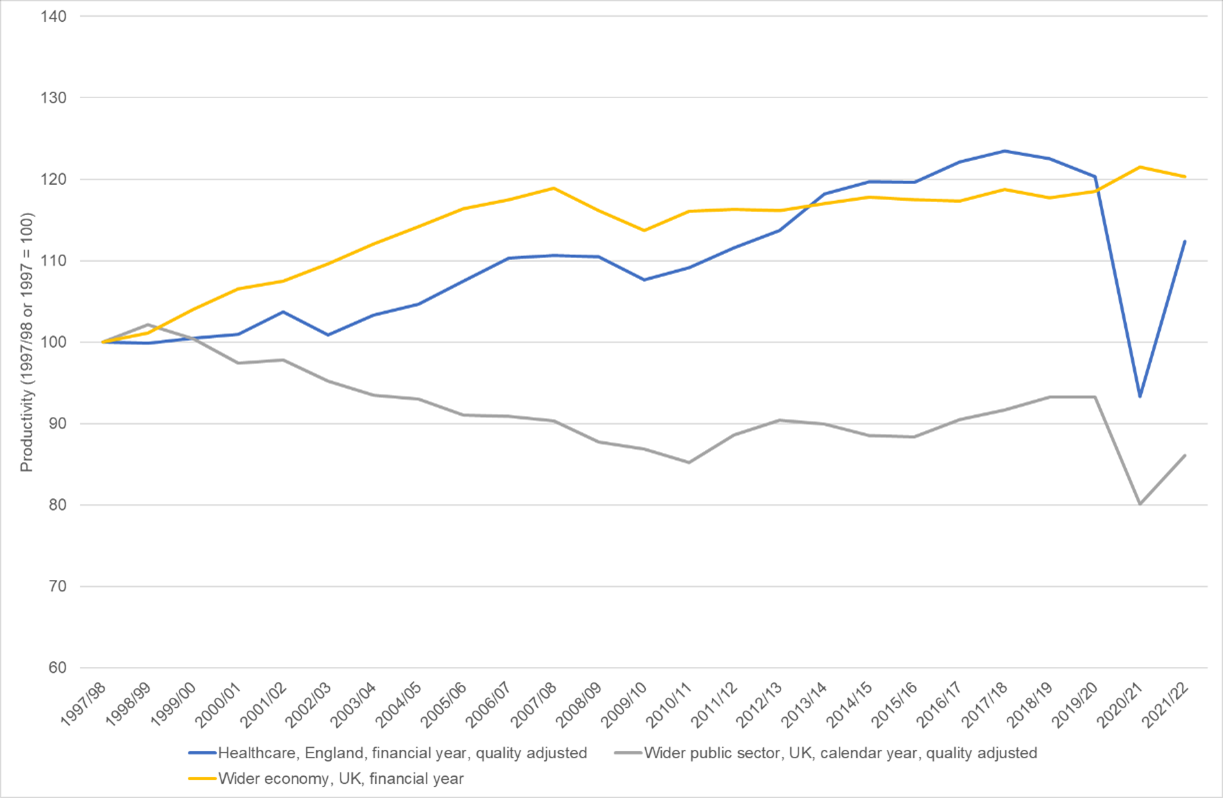

1. Pre-pandemic, the NHS typically delivered productivity growth at a faster pace than the rest of the public sector and the wider economy. In line with health systems across the world, the pandemic caused significant and long-lasting disruption to NHS services, and consequently productivity.

2. Productivity is difficult to measure across the public sector, and in the NHS specifically. Measures often do not capture the full range of patient related quality and outcomes that are delivered, especially when models of care are changing. However our best estimates of productivity from acute sector data suggest productivity from 2023/24 is still lower than it was pre-pandemic. This paper explores the factors driving this and the emerging plan to improve this position.

Figure 1 – Office for National Statistics productivity estimates from 1997/98 to 2021/22 [1]

[1] Public sector healthcare productivity statistics published for financial years, England only, quality adjusted. Source: ons.gov.uk

Wider public sector productivity published for calendar years only, for the UK, quality adjusted. Calculated by subtracting public service healthcare productivity from total public sector productivity. Source: ons.gov.uk

Wider economy productivity statistics published for financial years, for the UK. Estimates are for multi-factor productivity. Source: ons.gov.uk

3. Research has been done by think tanks, NHS England and local NHS organisations to understand what happened to productivity during and since the pandemic. The drivers of what we observe in data are complex, but include some key factors:

- Reduced resilience going into the pandemic. NHS operated as a very lean system pre-pandemic, with very little spare capacity to absorb shocks such as covid, compared to other countries. Real terms reductions in capital investment had meant a growing backlog of maintenance and increasing technology debt. The Real Centre at Health Foundation (Diane Coyle, Dec 2023) argues that “The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic makes it clear that, considered as core infrastructure, the NHS did not have enough spare capacity”.

- Population needs are more complex and acute. Data analysis shows a marked increase in complexity in admitted patients in acute hospitals, in part due to the fluctuating incidence of covid-19.

- Reduced flow through the urgent and emergency care pathway and across the system. Longer lengths of stay combined with constrained capacity (in and out of hospitals) means lower throughput.

- Post-pandemic turnover in experienced leadership and management alongside a necessary increase in staff coming through junior grades [2].

- Staff burnout and lower engagement. Sickness absence rates have reduced from the high point during covid, but are still higher than 2019 levels with an increasing proportion with stress related absences. Industrial action in 2023 continuing into 2024 has also contributed to higher costs and reduced productivity.

[2] According to a new Nuffield publication (2024), the proportion of new nursing registrants (less than a year on register) nearly doubled from one in 27 in 2018 to one in 14 in 2023. Non-UK nurse joiners also doubled in proportion from 21% six years ago to 42%. There are also more younger staff, with over a third (34%) of all nurses and midwives under 35, compared to 28% in 2015.

Overall NHS productivity

4. The most authoritative source for data on NHS productivity performance is the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Their definition of productivity measures how well the NHS turns a volume of inputs (eg staff, drugs, medical equipment) into a volume of outputs (eg surgical procedures, GP consultations, outpatient attendances).

5. It does not, however, fully capture wider benefits, such as where patients can receive the same or better care in less intensive healthcare settings. Examples include performing procedures in an outpatient rather than admitted care setting, or increasing the spend on preventative services to avoid costly care in hospital settings – both of which can improve patient care and patient experience at lower cost. The ONS measures tend to be produced with a 2-year time lag in order to use the most comprehensive data sets. The most recent data for overall NHS productivity is for 2021/22. It shows that after a sharp fall in 2020/21 there was significant recovery of overall productivity in 2021/22 though it was still 6.6% below the pre-pandemic level (see figure 1). The official ONS data for 2022/23 has not yet been published. ONS have produced an experimental method which would suggest further improvement in 2022 with overall NHS productivity between 5.5% lower and 2.7% higher than in 2019.

Acute hospital productivity

6. NHS England has conducted analysis to look specifically at productivity in the acute sector using in-year data. The aim is to understand the drivers of changes over the last 4 years in the acute sector, to inform future planning and investment discussions, and to support providers in identifying areas for quality improvement. There are limitations using in-year data including: incomplete coverage of acute activity (outputs), problems in separating out costs and staffing between acute and community services for integrated trusts, and fully accounting for complexity or quality improvements [3]. Some of these limitations can be overcome with the annual detailed cost collection.

[3] NHS England analysis uses HRG 4 character weights (recording procedures, type of procedures per admission/attendance) to calculate productivity due to data lag, whereas ONS productivity analysis weighs activity at HRG 5 character level (recording morbidity and complications).

7. Given the limited scope and data constraint of this analysis, it is not directly comparable with the overall productivity analysis ONS conducts referenced above.

8. Where possible we have to take account of:

- Expanding coverage of activity combining different data sources where possible, such as maternity, critical care and advice and guidance. However, this analysis has yet to be able to include all acute activity such as diagnostics activity. Missing out on such activity could have a negative impact on productivity given outputs growth is not captured while inputs growth (costs) has been.

- Service changes where productivity measurement lags behind such as advice and guidance, same day emergency care expansion, where investments have been made to deliver equivalent care in other settings or to avoid unnecessary activity.

- Increases in the acuity and frailty of patients admitted to hospital as emergency cases who have on average a longer length of stay than the historic norm. This has the effect that there is lower throughput which traditionally is reflected as lower productivity for a given resource. Initial analysis indicates that complexity explains half or more of the increase in length of stay of emergency admissions.

- The NHS is also not operating under the same conditions as in 2019/20 as covid has resulted in additional processes and resource commitment which include an increased level of infection control and vaccination requirements, and this has a direct impact on productivity from an input side, the estimated impact on the current productivity level is at least 0.6%.

9. 2023/24 was also significantly impacted by industrial action. It had direct costs of around £1.2 billion and reduced aggregate activity. We estimate an impact on productivity of around 3%. Based on this analysis, adjusted productivity (taking into account the above) would be around 11% lower than before the pandemic or 8% if we adjusted for the impact of industrial action.

10. We can measure some of the factors that are driving this position:

- The increase in depreciation and cost of capital charges as the NHS is recapitalised after real terms reductions in investment in the prior decade. The Government has funded the NHS to invest in new capacity (diagnostic, surgical hubs, bads and hospital upgrades, electronic patient records). These generate in-year costs as they start that we expect to deliver productivity gains in future years.

- Length of stay for non-elective patients has increased during and since the height of the pandemic beyond the observable impact of case acuity. This has had a number of causes including: disruption to operational processes, constraints on out of hospital capacity in particular social care where domiciliary care capacity has been recovering since 2022.

- Each year there are new branded medicines and high cost medical technologies that are commissioned that improve treatment outcomes with increasing costs. The improved outcomes are not captured in the in-year data but the costs are captured.

- Temporary staffing costs are still higher than pre-covid, partially to cover higher sickness and absence rate among staff, in addition to covering for industrial action.

11. These factors explain around half of the residual gap and identify areas where we are focused on improvement including: delivering the benefits of investment; improving staff engagement and attendance while focusing on reducing expensive agency costs; improving flow through hospitals and working with all partners in integrated care systems to ensure there is the right capacity in the right place to care for patients effectively.

12. This still leaves a gap which we cannot yet explain from national data. In particular, we cannot yet estimate the impact of reduced staff discretionary effort as we have come through the pandemic and industrial action. Ward fill rates have improved which should help impact on staff welfare and retention, patient safety and therefore longer-run productivity. We also know that in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic we saw a spike in the leaver rate as some of our most experienced staff who had stayed through the peak of the pandemic retired. The increased demand on existing clinical staff to train and develop newer staff will have benefits in the longer term but also has an impact on productivity in the short term.

13. As our population continues to age and more people are living with multiple long-term conditions, patients are staying in hospital longer, accessing primary and community services in higher volumes, and needing more complex physical and mental health care. The result is record NHS demand, creating additional pressure on an NHS workforce still recovering from a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic.

14. Despite these challenges, and in particular the challenges created by industrial action, improvement has been made this year and further recovery is possible:

- Implied productivity in the acute sector is 1.2% higher than 2022/23 (M11 YTD), with output (cost weighted activity) being 5.8% higher.

- Spending on agency has reduced from £3.5 billion in 2022/23 to £3 billion in 2023/24, which represents a 13% reduction. Agency spending was 3.6% of the total NHS pay bill, representing the lowest level of agency spending (as a proportion of pay) since at least 2017/18 when comparable data reporting started.

- Day case rate (BADCS rate) is now at 81% compared to 78% pre-covid; capped theatre utilisation is 79% vs 75-76% pre-covid.

- Over 3 million urgent suspected cancers referrals were seen, up 5% on 2022/23, meaning a higher proportion of people are now being diagnosed with cancer at an early stage when the disease is easier to treat.

- Record numbers of GP appointments are being delivered with 2.5 million more patients seen a month compared to May 2023 (when the primary care access recovery plan was published).

- Shifting care into less intensive settings. For example, compared to 2022/23, 700,000 more referral to treatment pathways are being completed in non-admitted settings.

- On the urgent and emergency care pathway, there has been a continued effort to avoid overnight admissions and reduce discharge delays, with 11% more patients admitted and discharged on the same day and a 3% decrease in average length of stay for those staying overnight compared to 2022/23.

Recovering productivity and improving care

15. We know there is more to do as the NHS recovers to create the environment for sustainable productivity improvements into the future increasing annual improvement towards 2% a year by 2029/30. NHS England are developing a short, medium and long-term productivity plan with further details to follow in the summer.

16. The key areas of ongoing focus include:

17. Operational and clinical excellence – adopting best practice across NHS services to reduce unwarranted variation. This not only translates to better and faster care for patients, but better value for taxpayers. Optimising processes means staff spend more time providing care. To deliver this we are:

a. Building leadership and organisational capacity and capability to deliver improvement through NHS IMPACT as our single improvement approach for supporting systems and providers with continuous improvement.

b. Continuing to expand Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) methodologies, which now cover more than 40 surgical and medical workstreams. For example, Further Faster pilots across 19 specialties at 49 trusts showed that the 52-week backlog reduced by as much as 36% across the first cohort of trusts compared to 11% among non-participating trusts.

Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust introduced a high-volume low complexity cataract surgery list as part of GIRFT – treating up to 10 patients per theatre list, almost double the previous number. This has had a positive impact on the elective backlog.

c. Driving adoption of less clinically demanding treatments, such as the world-first rollout of subcutaneous immunotherapy for lung cancer that cuts treatment time by 75%. Rapid adoption of direct oral anticoagulants – that don’t require frequent blood monitoring – have seen hundreds of thousands more people taking required anticoagulation treatment, saving thousands of lives and preventing many thousands more strokes, that would lead to downstream care demands.

d. Continuing to tackle interventions of limited or no clinical value – the evidence-base interventions programme, a clinically-led programme led by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges in partnership with NHS England [4].

[4] The programme has saved £200 million in its first year and in the financial year 2022/23 ensured 500,000 inappropriate or unnecessary interventions were avoided In one example, exercise electrocardiogram (ECG) for screening coronary heart disease was recommended as having no role in screening asymptomatic and low risk patients. For people at low risk of CVD, the potential harms of screening with exercise ECG is thought to be equal to or exceed the potential benefits.

18. A healthy motivated and engaged workforce – we have lost some of our most experienced staff at a higher rate since the pandemic, and have felt the impact of strikes, staff sickness and burnout. We know a thriving workforce enjoys better opportunities for training and development, and in turn uses their full range of skills in the delivery of their roles; and evidence shows an engagement workforce is more productive. To tackle this and to put our workforce on a longer term more sustainable footing we are:

a. Implementing the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan – listening to staff to improve, flexible working practices, optimising skills to better meet needs, developing a management culture and focus on improvement.

b. Improving how we deploy our staff to meet the needs of patients and maximising the use of valuable staff time, reducing the need to rely on expensive agency staff when it can be avoided.

c. Improving staff engagement and retention, enabled by the National Retention Programme which works with cohorts of organisations (expansion to 116 organisations in 2024), through targeted interventions, including flexible working, pensions support, health and wellbeing and career conversations which have resulted in a reduced leaver rate and increased staff engagement. Resolving industrial action is critical to achieving all of this.

Next steps

19. Work is underway on a detailed plan to cover all aspects of productivity improvement with a further update to follow in the summer, including on the areas below.

a. Focussing on health rather than illness – this means investing in preventative care, keeping people independent for longer and caring for people as close to home as possible. This includes targeted secondary prevention on modifiable risk factors, national prevention programmes such as diabetes prevention and digital weight management, and developing new models of care to shift care upstream.

b. Embracing 21st century technology – investing in IT systems that work well for both staff and patients, putting technology in the hands of patients to improve their access and experience, using our data to identify opportunities for improvement, and adopting new technologies that revolutionise care. For staff it means less time spent chasing patient data, or waiting for their technology to work – whether the most basic tool, or innovative product.Work is underway to set out the plan to deliver the ambitious programme as announced in the Spring Budget.

c. Maximising value for money – taking action such as cutting duplication, while for the patient it means less time waiting for treatment and for the taxpayer. This will leverage both national opportunities that leverage NHS’s collective purchasing powers, as well as leveraging local forums for staff and patients to identify and tackle waste.

20. A critical dependency of productivity improvement is modernisation of NHS facilities. This means addressing the maintenance backlog to reduce disruption. Failing to invest in our ageing estate will mean increasing instances of incidents that result in lost clinical time, such as electrical faults and leaks – there have been 12,000 reported estate failures that have stopped clinical services over the past two years’ alone. Integrated care systems are being supported to develop 10-year infrastructure strategies with a focus on how the NHS estate’s cost-effectiveness, productivity and efficiency can be increased and long-term running costs can be reduced.

21. Combined, these actions will enable the NHS to meet the commitments made in the Spring Budget to increase NHS productivity growth to an average of 1.9% from 2025-26 to 2029-30, rising to 2% over the final 2 years.

22. This will also require undertaking work to ensure we are capturing the benefits in the calculation of productivity where the service delivery model is changing (for example undertaking more surgical procedures in an outpatient setting) and where more care is being delivered upstream, or in prevention activities. This will be critical to ensure that the ‘right’ productivity is being delivered, and the transformation to services being delivered by our workforce which have the greatest impacts on patient outcomes are being fully valued in our productivity calculations.

Publication reference: Public Board paper (BM/24/19(Pu)