Annex A – Supplementary information about the offender personality disorder (OPD) pathway

1. OPD pathway high-level aims

The four high-level aims of the OPD Pathway are:

- A reduction in repeat, high-harm offending.

- Improved psychological health, wellbeing, pro-social behaviour and relational outcomes.

- Improved competence, confidence and wellbeing of staff working with people in the criminal justice system showing personality difficulties.

- Increased efficiency, cost-effectiveness and quality of OPD pathway services.

Note: Aim 1 ‘A reduction in repeat, high-harm offending’: evidence/measure of success would include longer time of success in the community and decreased severity of offences.

2. OPD pathway intermediate indicators

The intermediate indicators for the OPD pathway are:

- Improved access and progression through services for service participants.

- Improved understanding by staff and service participants of behaviour, risk factors and strategies to manage these effectively.

- Reduction in number and severity of incidents of general and violent misconduct.

- Reduction in number and severity of incidents of self-destructive behaviour.

- Improved quality of OPD pathway services through meaningful involvement of service participants.

- Improved quality of the relational environment in OPD pathway services.

Note: For the purposes of this document, service participant refers to people who are participating or residing in OPD pathway services, who may be prisoners, people on probation or patients in secure hospitals.

Short, medium and long-term outcomes are set out in the pathway’s theory of change (see Annex C), which details the chain of events and further outcomes when considering service participants, staff and the wider system.

3. Summary of OPD pathway evidence base

Most research and evaluation across the pathway to date has been qualitative, giving promising indications of successful implementation and insight into the potential mechanisms of change. Future evaluations will focus on impact and outcome across the OPD pathway. While these will emphasise rigour, careful consideration will be given to the design of all evaluations, particularly in relation to data limitations and real-world research. However, evaluation of the OPD pathway has added challenges, including the difficulty of finding an appropriate control group and of incorporating mental health needs, as so far it has not proved possible to link health and justice administrative datasets.

Due to the timescale of operation of the OPD pathway, the heterogeneity of delivery (that is, the range of different types of service and the level of involvement of any one individual) and the complexity of doing research and evaluation using reoffending data, it is deemed too soon to look at whether the pathway is achieving its high-level outcomes.

While there are still areas of the OPD pathway to be evaluated, the literature available indicates a range of beneficial outcomes for prisoners with complex needs accessing services such as democratic therapeutic communities (DTCs) [1] and psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs). Elements of delivery in the community, including case formulation and training for probation practitioners in psychologically-informed practice, have also demonstrated positive impacts on overall probation practice.

Key evaluation findings across the pathway

- Most case formulation evaluation focuses on workforce outcomes. Some studies described consultation and formulation services as helpful and informative for practice development, while others noted the main benefits relate to emotional support and validation, rather than to more applied aspects affecting risk management. [2] [3]

- Evidence is being built in relation to formulations. [4] Most recently, potential factors associated with positive outcomes have been identified in formulations and their recommendations. [5]

- Operational staff have noted improvements in their understanding of ‘personality disorder’ and reported feeling more competent and confident in working with complex individuals. There is evidence that formulation training contributes to these improvements. [6]

- Other studies report mixed findings for the quality of formulations post training [7] with one study reporting no difference when looking at competence. [8]

- The OPD pathway national evaluation carried out a mixed methods, process and impact evaluation for men across the pathway [9], and a separate evaluation for women which it also plans to publish. A cost-benefit analysis was also attempted for the male pathway. The national evaluation for men has provided positive evidence regarding the implementation of the pathway and how it has been received by staff, prisoners and probationers. However, further work is needed to demonstrate the pathway’s outcomes in a robust, quantitative analysis. Key findings from the qualitative evaluation were:

- establishing trust and collaborative work was key to the work of the pathway for both staff and service participants

- service participants felt their risk had reduced and psychological health had improved, and that they felt safer

- staff spoke highly of the training and supervision provided (a finding replicated in an evaluation looking at PIPEs).

- Across OPD intervention services, studies have found evidence of higher social climate levels. [10]

- Qualitative evaluations have indicated PIPEs can impact on the ‘relational’ environment in a positive way, including service participants’ feelings of emotional safety [11] and relational thinking styles. [12].

- Kuester et al [13] found in a mixed-methods evaluation looking at progression PIPEs that:

- service participants reported better social and relational skills than comparator prison wings, with significantly lower levels of problematic social problem-solving and relating styles

- qualitatively, staff and service participants reported improved relationships. Service participants engaged in pro-social behaviour, corroborated by staff who felt they had reduced their use of force.

- In a small-scale study looking at an enhanced support service (ESS) intervention, ESS appeared to significantly reduce post-intervention verbal aggression. [14]

- A number of publications looking at the impact of the intensive intervention risk management service (IIRMS) model suggest positive outcomes for service participants in the community, including a randomised controlled trial showing lower self-reported rates of antisocial behaviour. [15] [16]. While the trial did not observe significant changes in proven reoffending, a more recent study found a notable absence of serious further offences post-intervention. [17]

- A study exploring the impact of psychologically informed practice in two supported housing hostels found significantly lower reoffending rates among those in receipt of supported housing in comparison to those receiving outpatient-only intervention. [18]

4. The relational environment

The social and therapeutic environment is an important part of any service; however, there is a particularly strong emphasis on this in services for people with complex psychosocial difficulties who may satisfy a diagnosis of ‘personality disorder’. The OPD pathway makes conscious use of the social environment and relationships between staff and participants as a method for change in its own right; this can be considered to be a ‘planned’ environment. OPD pathway services have a focus on relationships, paying particular attention to quality and consistency, and using every opportunity for people to have safe and meaningful interactions in both formal and informal settings.

To provide quality and consistency in experience of relationships across the pathway, all residential and intervention services in the OPD pathway are expected to work toward the enabling environments standards. The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Centre for Quality Improvement developed the enabling environments standards as a quality improvement mechanism to support services to increase their use of therapeutic principles for the creation of positive living and working environments. It is a standards-based award that supports the establishment of a supportive, positive relational environment.

For further information, please see: Values and standards: what are enabling environments?

5. Workforce development

Workforce development is one of the four high-level outcomes for the pathway and a separate OPD pathway workforce strategy is in place. Ongoing staff development and training are designed to help staff develop the skills, confidence and therapeutic optimism needed when working with complex individuals likely to meet the criteria for diagnosis of ‘personality disorder’.

His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS)/NHS England Practitioner guide: working with people in the criminal justice system showing personality difficulties, originally published in 2011 and updated in 2015 and 2020, provides practical support and advice for staff in how to respond effectively to the complex individuals in their care, and in how to manage themselves and the systemic tension that emerges from the work.

The cornerstone for workforce development remains the personality disorder knowledge and understanding framework. This framework was designed to meet the needs of all staff who may come into contact with prisoners or people on probation likely to satisfy a diagnosis of ‘personality disorder’, and it retains a layered approach to workforce development through awareness, certificate and BSc/MSc level. The framework continues to offer tailored approaches to meet the needs of particular staff groups (eg those working with women).

6. Involvement

The OPD pathway has a separate involvement strategy, which aims to include individuals accessing and working in services in all aspects of service design, delivery and review in line with the pathway’s underpinning partnership ethos. It is recognised that meaningful involvement has transformative potential in reducing reoffending and improving psychological wellbeing. Three key underpinning theoretical models for service delivery under the auspices of the pathway are attachment theory, psychoanalytic theory and desistance theory. These models emphasise the importance of relational working, strengths-based approaches, and therapeutic optimism and alliance when working with individuals experiencing significant ‘personality difficulties’ who also present a significant risk to others. Meaningful involvement of staff and participants within services is seen as being integral to this approach. As such, the requirement for services to support involvement is specified in the OPD quality standards framework (see Annex D).

7. Transgender people and the OPD pathway

Prisoners who are transgender, gender-fluid, gender-neutral, intersex or non-binary are screened for the OPD pathway according to the estate in which they are located. The exception to this may be where an individual with a gender recognition certificate is held in a prison that does not match their legal gender, to manage risk as determined by a complex case board. In such cases, advice should be sought from the regional psychology lead.

Where the person is in the community, OPD pathway screening will be applied based on legal gender. Screening override can be used, where appropriate.

Annex B – OPD pathway service types and definitions

1. The OPD pathway approach

The OPD pathway approach aims to ensure that a person’s risk to others is effectively managed – and where possible, reduced – throughout their sentence. It is a community-to-community approach that has multiple benefits:

- It acknowledges the reality that someone may not engage with all the services available to them at any given time and that they may move back and forth across the pathway throughout their sentence (or indeed, their lifetime). As a result, the aim is to offer comprehensive services at each stage of a person’s journey, irrespective of whether they have previously failed at some point on their pathway.

- Each OPD pathway service is underpinned by the pathway’s high-level aims, principles, service specifications and quality standards. As a result, services share the same aims in relation to this group. This means that people can be offered consistency and support throughout their time on the pathway without stifling innovative ways of working.

- The pathway approach builds on current evidence that suggests that a bio-psycho-social approach, encapsulated in a formulation – in which management, cognitive, social and pharmacological interventions may play their part – is the best and most consistent approach with which to develop a coherent and consistent narrative of an individual’s problems, and manage a pathway for this population.

- Every effort is made to create local, regional and national pathways where possible, to augment and support existing services and processes, with the aim of ensuring that those meeting the OPD pathway entry criteria are able to access appropriate service provision regardless of geographical location and offence type.

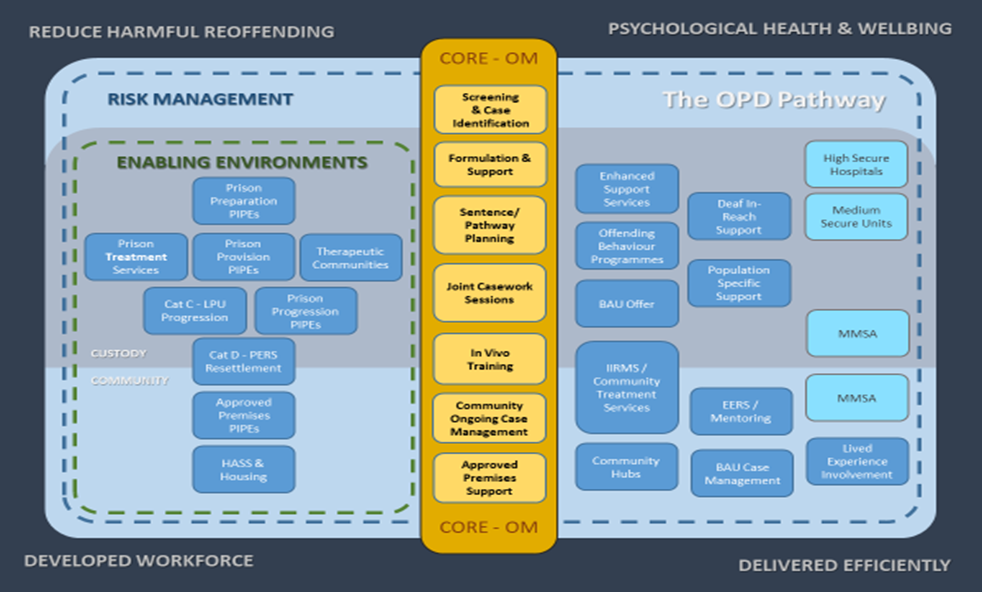

Figure 1: illustrates how the various interventions of the OPD pathway fit together

2. Stages of the OPD pathway

The first stages of the OPD pathway involve identifying those who meet the entry criteria and developing an appropriate pathway plan for them. This activity is delivered, for those in the community, by community probation practitioners working in local probation delivery units (PDUs); and for those in prisons, by prison probation practitioners, with both groups working in partnership with a health service provider (in the community) or local His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) psychology practitioners (in custodial settings).

Early identification

Early identification describes the process of identifying, at the earliest possible opportunity, those cases that meet the criteria for the pathway. This should happen post sentence for new cases once the HMPPS Offender Assessment System (OASys) assessment is complete. The purpose of early identification is to plan for people through consultation and formulation, and to help them progress against their sentence plan. Probation staff receive training as part of the workforce development strand of the pathway to assist with this process and have access to case consultation, usually provided by a forensic or clinical psychologist. The identified caseload includes those who are newly sentenced as well as those who are already held on the caseload. Probation practitioners in both prisons and the community work in partnership with staff from the health service provider or HMPPS psychology service to discuss individual cases in more depth and decide whether someone meets the pathway criteria.

Case consultation and formulation

Once an individual has been identified as meeting the criteria for the pathway, the probation practitioner works in partnership with the health service provider or HMPPS psychology staff in the prison setting to develop a pathway/sentence plan for the person based on a process of case consultation and formulation. Case consultation and formulation describes a joint process of targeted specialist advice and discussion between health and criminal justice professionals, including the prisoner, person on probation or patient in secure hospital, where possible, to consider their psychosocial and criminogenic needs relating to their complex psycho-social difficulties, and to make timely decisions about their sentence plan. Case formulation is always recorded but varies in style depending on the complexity of the case and the urgency of the pathway plan. The offender personality disorder pathway has developed a set of standards for its formulations, dependent on complexity.

Pathway plan

The formulation should be used to ensure the sentence plan reflects the psycho-social and criminogenic needs identified through the consultation and formulation process. The timing of when someone receives any OPD services indicated in their plan may vary depending on their needs (eg a newly sentenced prisoner with a very long custodial sentence may not be prioritised for receiving OPD pathway services immediately within their plan). Some people may not receive specific OPD pathway services as they may be referred, and accepted, into mainstream health and criminal justice services. The plan is monitored and updated by the prison or community probation practitioner as necessary throughout the term of the person’s sentence.

It is anticipated that a significant number of people meeting the pathway criteria will be unwilling and/or unable to participate in services. In these circumstances, the formulation will focus on the effective management of the individual. This might include, for example: risk assessment; community case management; helping the individual develop insight, motivation and engagement; and supporting the person’s compliance with licence or sentence conditions. It is also likely that a large number will not require any additional services as business as usual activity would be sufficient to meet their needs.

The case consultation, formulation and pathway plan determine the appropriate management approach and interventions required for each person, and help ensure that referrals are made to services at appropriate times. Someone may be referred immediately to a treatment service or may engage in other services that help them prepare for formal treatment, such as a preparation psychologically informed planned environment (PIPE) or motivational interviewing. It should be noted that someone may be referred to a range of services as part of their pathway plan, and not just those commissioned by the OPD pathway.

3. OPD pathway services

OPD pathway services are evidence based and aim to ensure an improvement in mental and emotional wellbeing, social circumstances and community ties, associated with a reduction in risk of high harm offending. Service delivery is intended to take place within a safe, supportive and respectful environment, employing a range of skilled, motivated, supported and multidisciplinary staff to address a person’s personality difficulties and behaviours. The types of services co-commissioned by the OPD pathway can broadly be split into the categories below. Although not a service type, workforce development runs through all service types, both residential and non-residential.

|

Service type |

Indicative length of stay |

Residential service |

Non-residential service |

|

Core offender management services |

|

|

|

|

Identification, consultation and formulation: to identify individuals who meet OPD pathway criteria and to support staff working with them |

Ongoing |

|

✔ |

|

Joint case work with the case holder probation practitioner |

1-6 sessions |

|

✔ |

|

Custody interventions |

|

|

|

|

Prison outreach enhanced support services |

6 months 12 weeks |

|

✔ ✔ |

|

Psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs) |

6 to 24 months |

✔ |

|

|

Treatment services |

12 to 48 months depending on level of security/ need |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Democratic therapeutic communities (DTCs) |

18 months min |

✔ |

|

|

Democratic therapeutic community+ (TC+) |

36 months min |

✔ |

|

|

Pathway enhanced resettlement services (PERS) |

6 months |

|

✔ |

|

Medication to manage sexual arousal (MMSA) service |

Dependent on treatment plan |

|

✔ |

|

Community interventions |

|

|

|

|

Intensive intervention risk management services (IIRMS) |

12-18 months |

|

✔ |

|

Approved premises PIPEs |

3-6 months |

✔ |

|

|

Housing and accommodation support services (HASS) |

12-18 months |

✔ |

|

|

Enhanced engagement and relational support services (EERSS) (mentoring and advocacy) |

12-18 months |

|

✔ |

|

Mentalisation based therapy (MBT) service |

12 months |

|

✔ |

|

Medication to manage sexual arousal (MMSA) service |

Dependent on treatment plan |

|

✔ |

|

Hospital intervention |

|

|

|

|

Medium secure units (MSUs) |

6-24 months depending on complexity/ engagement |

✔ |

|

Core offender management (core OM) service

Central to the success of the pathway-based approach is psychologically informed case management by the probation practitioner in prisons and the community, and the provision of post-sentence arrangements to ensure the improvements made through interventions are sustained and ongoing risks are appropriately managed and monitored. The service provides:

- case identification (screening the caseload to identify those cases meeting the OPD pathway criteria)

- case consultation and case formulation

- workforce development

- time-limited joint casework by the probation practitioner and health service provider for a small number of people in the community with the most complex needs

- provision of support and advice to services delivering support to people as their statutory involvement with probation comes to an end.

Custody interventions

Outreach services

Prison outreach services consist of jointly delivered approaches to enhance work with:

- the most challenging and disruptive prisoners

- those who would benefit from preparatory support to enable participation in longer-term interventions

- prisoners post-intervention.

Enhanced support services and the Eos service below are specific types of prison outreach.

Enhanced support services (ESS): ESS are prison-based services that aim to reduce both the psychological distress of a highly complex and challenging cohort of prisoners, and the negative impact of their violent, disruptive and self-injurious behaviour. This is achieved through the use of a dedicated multidisciplinary staff team, working in partnership across prison, healthcare and forensic psychology services. ESS target the minority of prisoners in each establishment who demonstrate severe and persistent behaviour and who have not responded to existing strategies and interventions. Staff work intensively with these prisoners in a collaborative manner to help them develop motivation and positive coping skills. Staff also support individuals to work towards personal and sentence planning goals. Staff work in a psychologically informed manner and are supported by case formulation, which is based on an understanding of the prisoners with whom they are working. The team also works indirectly with other staff to increase understanding and appropriate management of these prisoners.

The Eos service: commissioned at HMP Bronzefield, Eos is a pilot service that uses a mentalisation-based therapy (MBT) approach to respond to the needs of a small group of people in the women’s prison estate whose personality-related difficulties and behaviours are so complex that they are unable to participate in OPD pathway interventions, such as a treatment service or PIPE.

Psychologically informed planned (PIPEs) environments

Psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs) are specifically designed environments where staff members have additional training to help them develop an increased psychological understanding of their work. This understanding enables them to create an enhanced safe and supportive environment, which can facilitate the development of those who live there. PIPEs are designed to have a particular focus on the environment in which they operate, actively recognising the importance and quality of relationships and interactions. This is called a relational environment. They aim to maximise learning opportunities within ordinary living experiences and to approach these in a psychologically informed way, paying attention to interpersonal difficulties; for example, those issues that might be linked to ‘personality disorder’. PIPEs do not provide formal treatment but are specifically designed to support people to progress through their pathway. The following types of PIPE are offered as part of the OPD custodial pathway:

- Preparation PIPE – to help someone prepare for the next step of their OPD pathway plan, which is usually, but not always, a treatment environment. Preparation PIPEs are for prisoners who have difficulty progressing to the next stage without additional support.

- Provision PIPE – where someone resides in a PIPE environment but participates in an intervention elsewhere, eg off the wing; provision PIPEs are designed to help with adherence to treatment programmes, as well as offer an opportunity for additional support.

- Progression PIPE – for people who have completed a high intensity treatment programme (men) or other relevant risk focused work (women). They offer the opportunity to put these skills into practice.

OPD treatment services

OPD treatment services are delivered in prisons and in the community for both men and women. Typically, these include a range of psychological approaches, are delivered over a number of months or years by specially trained clinicians and criminal justice staff in an environment that is safe, supportive and respectful. Residential treatment services can also provide services reaching into their host establishment.

Democratic therapeutic communities

Democratic therapeutic communities (DTCs) consist of group therapy, one-to-one meetings and community living, where everyone in the community shares responsibility for its day-to-day running, decision-making and problem-solving. DTCs are an accredited HMPPS Offending Behaviour Programme but are known to be particularly effective with those who have personality disorder, and therefore play a key role in the OPD pathway. DTCs are provided in prison settings as part of the OPD pathway.

Democratic therapeutic community

Democratic therapeutic community + (DTC+) operates within the framework and model of mainstream DTCs in prisons; however, the approach is adapted to better meet the support needs of those with a serious offending history who have learning disabilities.

Pathway enhanced resettlement service

The pathway enhanced resettlement service (PERS) is specifically designed for people who are transferring to category D prisons. It is currently delivered in five open (category D) prisons. PERS provides support to prisoners who may find the transition into open conditions and safe release into the community difficult. It is recognised that many failures in open conditions arise from difficulties in relationships with family members, a sense of hopelessness about the future, and difficulty coping with the pressures of life in a less secure setting. PERS aim to reduce the risk of return to closed conditions and encourage successful integration into open conditions and then the community.

Community interventions

Intensive intervention and risk management services

Intensive intervention and risk management services (IIRMS) are community-based services delivering individually tailored and psychologically informed interventions directly to people who satisfy the criteria for the OPD pathway, to manage risk of serious harm and reoffending, and develop psychological wellbeing and social engagement. These services operate alongside other OPD pathway services in custody, community and health settings. Standard IIRMS deliver the basic elements of the specialist model, while enhanced IIRMS deliver more formal psychological therapies that can be offered in addition to the standard interventions.

Approved premises psychologically informed planned environments

Approved premises psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs) are community-based hostels supporting those who have been released from custody, by offering the same six core components of the PIPE model as the custodial PIPEs, including regular training and supervision for staff.

Housing and accommodation support services

Housing and accommodation support services (HASS) provide specialist accommodation to those who satisfy the entry criteria for the OPD pathway, thereby facilitating their eventual move to fully independent living in the community.

Enhanced engagement and relational support services (EERSS)

Enhanced engagement and relational support services (EERSS) offer an independent, flexible, needs-led, highly individualised support package to people in the community or those who are transitioning into the community from prison or hospital. Drawing on the principles of mentoring and advocacy, EERSS provide emotional and practical support, with particular emphasis on:

- motivation and engagement

- practical issues (including family)

- relationships (with family, staff and peers)

- navigating and accessing services (including education and employment)

- self-esteem and empowerment.

Workers, who may be paid staff, volunteers or peer mentors, provide experience of reliable relational support to service participants, which is consistent and continuous over time. Originally commissioned for women, EERSS is now being piloted for men in London, with a particular emphasis on men aged under 30 and men from minority ethnic backgrounds.

Mentalisation based therapy service

The mentalisation based therapy (MBT) service is for men who meet the diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) in the community. The treatment intervention comprises a 12-month programme of weekly group and monthly individual MBT sessions. The service is being delivered across 13 sites in England and Wales and treatment is delivered on probation premises. The co-ordination and management of the MBT ASPD services is led by the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, and initial training and ongoing supervision for treatment providers is provided by the Anna Freud Centre. The MBT service is part of a randomised controlled trial; this is the first large-scale trial of treatment for people on probation with ASPD and will provide key evidence to inform treatment decisions in this group.

Medication to manage sexual arousal (MMSA) service

The medication to manage sexual arousal (MMSA) service is delivered in a small number of settings in custody and the community, providing medication with associated psycho-social support to men who have been convicted of sexual offences, to help manage problematic sexual arousal and obsessive-compulsive sexual thinking. It sits alongside other services and interventions delivered as part of the criminal justice system or by the NHS or as part of other commissioned OPD pathway services. Service provision is not universally available currently. Entry to the service is determined by clinical need; service participants do not have to satisfy the entry criteria for the OPD pathway.

Hospital intervention

Medium secure units

The OPD pathway includes delivery of personality disorder intervention services in two medium secure unit (secure hospital) environments.

Criteria for hospital placement

Not all those who satisfy the criteria for the OPD pathway can be managed in the criminal justice system and therefore they will need to be transferred to a secure hospital. A hospital placement should be reserved for those who can only be managed in a hospital setting, and who are detainable under the Mental Health Act. Broad criteria that might suggest a hospital service is required are as follows:

- Uncertain or disputed diagnosis and risk; repeated failure in a prison setting; irretrievable breakdown of relationships in custody.

- Co-morbid mental illness, eg psychosis, depression with high suicide risk, which is not well-managed and requires hospitalisation for stabilisation.

- Complexity compounded by, for example, borderline IQ (IQ score between 75 and 85), with highly impulsive threatening and violent behaviour, deliberate self harm, uncertain or changing diagnosis or medication needs.

- Complexity added by other therapy-interfering behaviours, eg litigiousness, breaches of boundaries, pathological attachments.

- Complexity or need around neurological difficulties/acquired brain injury.

- Need for rare or bespoke intervention that is not readily available in prison.

Criteria for a prison placement might include:

- Prisoners who can be managed in a custodial setting and who have been identified as part of the OPD pathway.

- Well-managed complex co-morbid mental illness.

- Those who have failed in high secure hospital settings or who cannot be managed in hospital.

It is recognised that some people may move back and forth between health and prison settings, depending on their needs.

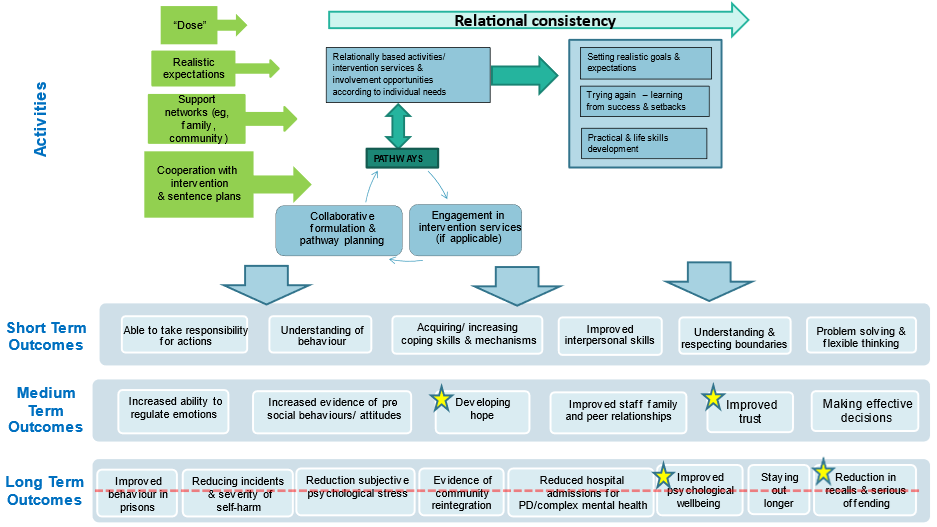

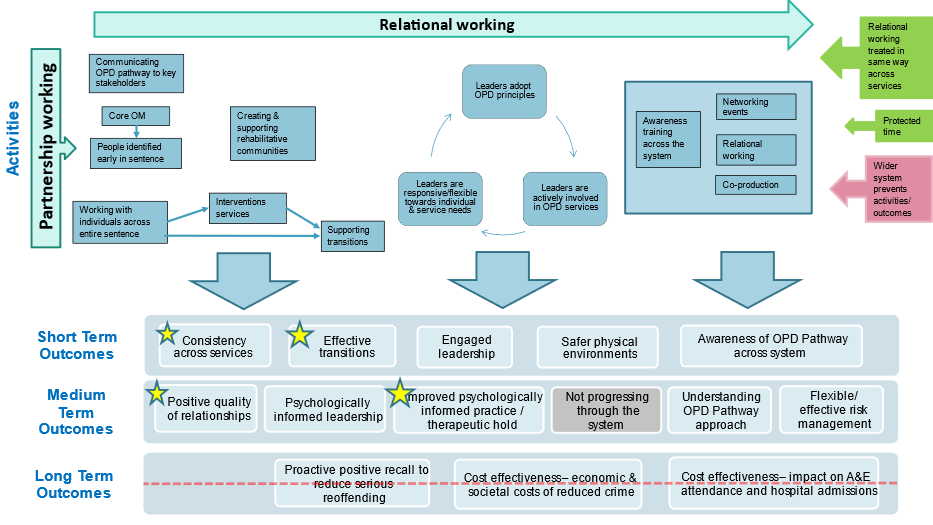

Annex C – OPD pathway theories of change: overarching, staff, service participant and systemic

In line with best practice for evaluation, a theory of change has been developed for the OPD pathway. It articulates the pathway’s theory in a clear, succinct way and shows the links between the activities and outcomes across the pathway, and the chain of events that may lead to its high-level aims.

A theory of change is a dynamic process that sets out the pathway of change a programme aims to achieve, via a series of logical steps.

It describes and explains how and why a way of working will be effective, what will be effective and when, and the possible mechanisms of change. The process provides an evidence-based framework and rationale for the OPD pathway; a pragmatic set of key activities that should be present to achieve change. This subsequently will be used to inform evaluation design.

The OPD pathway theory of change has been designed with the pathway’s primary stakeholders in mind:

- Prison and probation staff (in particular, probation practitioners and prison officers), whose focus is improving ways of working with, and managing, highly complex individuals.

- Service participants, who may be prisoners, people on probation or patients in secure hospitals.

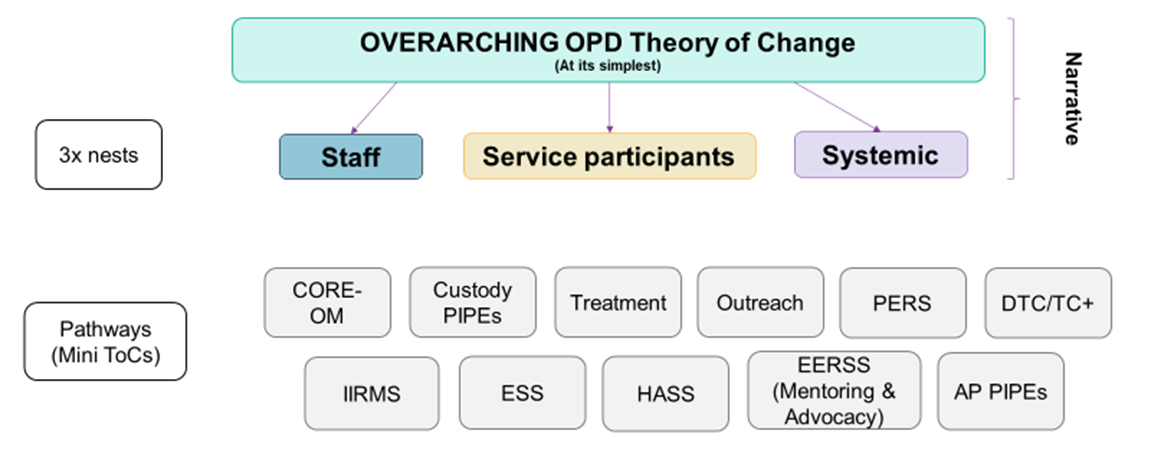

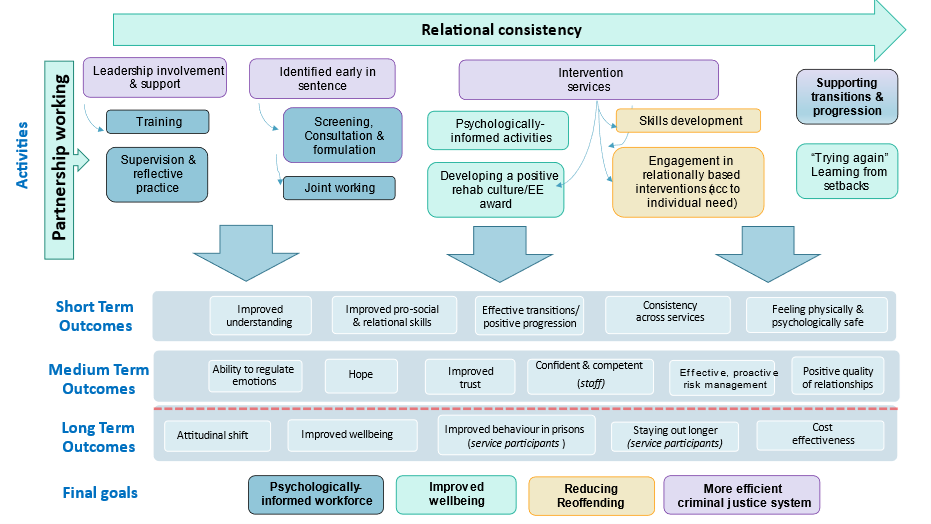

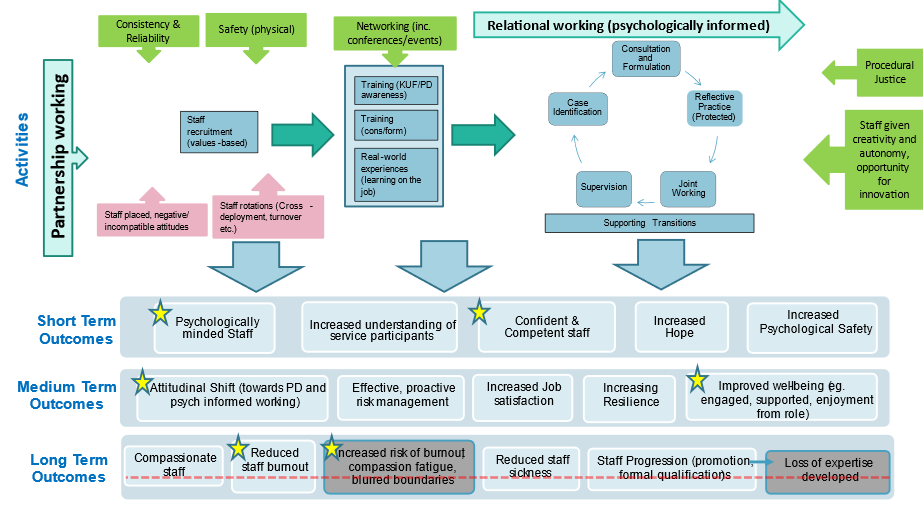

The OPD theory of change has been formulated at multiple levels to capture the multidisciplinary nature of the pathway, and to articulate how the various interventions contribute to the pathway’s outcomes. These levels are illustrated in Figures 1 to 5 below.

Figure 1(a) is a simple overview of each level of the OPD pathway where a theory of change has been or will be developed. The overarching theory of change for the OPD pathway is shown in Figure 2 and relates to the overall aims of the pathway. It is subdivided into three ‘nests’: two of these are applicable to the pathway’s key stakeholder groups: ‘staff’ (Figure 3) and ‘service participants’ (Figure 4). The final nest (Figure 5) takes a systemic view across the health and criminal justice sectors. All three nests are needed to achieve the overall aims and outcomes.

Figure 1(a): OPD theory of change – overview

Figure 2: OPD theory of change – overarching

Figure 3: OPD theory of change – staff nest

Figure 4: OPD theory of change – service participant nest

Figure 5: OPD theory of change – systemic nest

Annex D – OPD pathway principles and quality standards framework

1. OPD pathway principles

The OPD pathway is underpinned by a set of principles to which all OPD pathway services are expected to adhere. These principles reflect the evidence base behind reducing reoffending and addressing complex interpersonal problems that are likely to be diagnosed as ‘personality disorder’. Originally published in the 2015 OPD pathway strategy, the principles were refreshed in 2018 to ensure they continue to capture the fundamental aspects of the pathway.

There is shared ownership, joint responsibility and operations, and partnership working

Responsibility for this population is shared by the partner organisations, principally His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) and the NHS. Operations are jointly delivered wherever possible, demonstrating a collaborative culture in all aspects of service delivery. Partners value respective knowledge, skills and experience, and work together to overcome cultural and knowledge barriers.

There is a whole system, community-to-community pathway

Planning and delivery of services is based on a whole system pathway/continuity of care approach across HMPPS and the NHS. Services are a network underpinned by the same set of principles. This recognises the various stages of a person’s journey from sentence through prison and/or NHS detention to community-based supervision and resettlement. These individuals, based on need, are likely to require a long period of time over which to make progress and their care pathways are likely to be non-linear, cross-agency and to involve periods both in and out of services depending on need.

People on the pathway are primarily managed through the criminal justice system, with the lead role held by probation practitioners

People with severe, complex interpersonal problems that could be diagnosed as ‘personality disorder’ and who also present a high risk of harm to others will be primarily managed by HMPPS offender management arrangements; the lead role will always be the probation practitioner unless the person is detained under the Mental Health Act. Public protection remains the fundamental consideration in their management.

Treatment and management are informed by a bio-psycho-social approach, in which an individual’s development is understood

The OPD pathway operates a formulation-based approach, based on a bio-psycho-social understanding of the development of severe interpersonal problems likely to be diagnosed as ‘personality disorder’; it ensures a focus on the developmental history of the individual. This in turn helps inform the sentence plan, and places psychologically informed care at the centre of the required response from staff.

All services adopt a relational approach

The OPD pathway focuses on relationships and the social context in which people live – there are clearly described models in which staff understand the relational approach and the boundaries.

Staff have shared understanding and clarity of approach

Staff understand the underpinning models and approach to the work, their role and their responsibilities. Staff contribute to the design, development and review of services. Staff are trained and supervised where the knowledge and skills required for each staff group and individual within it are identified, and a plan is in place to ensure that these needs are met and reviewed. Individual and group supervision is provided, as appropriate.

The pathway is sensitive and responsive to individual needs, including gender, protected and offence characteristics

There is gender-specific provision and training; services for women take account of how gender differences influence the development of personality disorder, risk and psychosocial needs, to understand how services should be planned and delivered. Diversity and cultural needs are understood and acted on.

People, where directly engaged on the pathway, have clarity of approach

Service participants understand their role and responsibilities, and the nature of the work delivered. They can describe the commitments they have made, the requirements of them and their personal responsibilities within the service. Their health is improved by the work and their risk of reoffending and harm to the public is reduced.

There is meaningful involvement by participants in the design, delivery, performance management and evaluation of services

All people on the pathway have a voice and their involvement is actively encouraged. This complements and supports wider organisational aims around co-production and meaningful involvement of those with lived experience of services.

Ruptures and setbacks should be anticipated, understood and responded to as part of a formulation-based approach

The pathway approach is not linear for many people. Challenging behaviour and rule infractions and challenges to the system may lead to breaches of conditions of licence or community sentence, recall to prison, segregation in prison and re-categorisation. Treatment and management plans may not achieve the desired effect. Such breakdown and failure must be managed, ensuring that pathway plans are reviewed and revised to support future progression. Irrespective of whether people are actively engaging with services, they remain part of the pathway to manage risk, and staff will re-engage with them when they are ready.

There is shared learning across the pathway, involving staff and service participants

Both staff and service participants are encouraged to share experiences and learning related to the OPD pathway’s aims and outcomes; this includes taking part in peer review activities.

Services are developed in line with the model and using an evidence-based approach, where evaluation continually informs services

The pathway is evaluated robustly, focusing on risk of serious reoffending, health improvement and economic benefit. Services will be based on evidence where it exists, and the approaches used will drive innovation and the collection of new evidence wherever possible.

2. Quality standards framework

In 2018, following a refresh of the OPD pathway principles, a related set of quality standards was devised against which OPD pathway services can measure themselves and be measured. These standards are included in contracts and directly determine how data and qualitative information is reported to commissioners for performance review.

The OPD pathway quality standards framework underpins quality and gives assurance to commissioners and staff that services are being delivered to the highest possible standard with the funding available. Where evidence exists across health and criminal justice sectors, this has been used to develop and define the standards and to determine the qualities that are measured.

An overview of the themes and standards identified in the quality framework is outlined below. For each standard, further detailed criteria are in place, including how this will be measured.

Quality of the intervention as part of the pathway

- Q1: Appropriate individuals are identified against entry criteria for the service (including the pathway).

- Q2: Individual risk and need is understood and responded to.

- Q3: Therapeutic relationships form a critical component of service delivery.

- Q4: The pathway is sensitive and responsive to individual service participant characteristics.

- Q5: Individuals who meet the entry criteria move through a pathway of connected services that are identified in their pathway/sentence plan.

- Q6: The intervention is delivered according to the specification of the pathway and is evidence based or has a clearly developed model of change that is being tested.

Workforce training and supervision

- W1: Staff are trained to deliver their role with a clear understanding of the service and wider pathway.

- W2: There is sustained focus on staff wellbeing within OPD pathway services.

Operating conditions

- OC1: The physical environment is fit for purpose and used appropriately.

- OC2: Staffing of the service is appropriate to deliver the specification.

- OC3: Funding is used to provide the service as per the specification.

Partnership working

- P1: Appropriate information governance is in place and adhered to.

- P2: Partnership governance is in place and adhered to.

Involvement

- V1: The service promotes and facilitates authentic involvement throughout system design and delivery.

- V2: Involvement approaches actively consider the impact for service beneficiaries.

Enabling environments

- E1: An enabling environment is developed and maintained by recipients and providers.

Data, research and evaluation

- D1: Data is collected and recorded accurately and stored securely.

- D2: The service undertakes research and evaluation to explore and demonstrate their effectiveness and impact on OPD pathway aims and outcomes.

Commissioning

- C1: The OPD pathway is appropriately resourced and effectively managed to enable the delivery of OPD pathway aims and outcomes.

- C2: Contractual and financial arrangements are in place to protect and deliver OPD pathway services.

Annex E – Delivery timeline: OPD pathway strategy 2023 to 2028

1. Strategic objectives

Note: the priority objectives are indicated in bold font.

Ambition and objectives for 2023-24

- Pathway consistency-custody (A2.2): Commission a progression option suitable for those with learning disabilities by 2024 (priority).

- Inclusion (A3.2): Communicate national expectations for all OPD pathway services by 2024, as part of the national specification development, which support greater inclusivity of highly complex people while maintaining local autonomy according to service capacity (priority).

- Relational practice culture (A7): Refresh the OPD pathway involvement strategy by 2024, in response to the growing evidence base and practice, and to incorporate learning from the strategic review feedback received from OPD pathway staff and service participants (priority).

- Relational practice culture (A7): Review and update the OPD pathway workforce development strategy by 2024, to support and respond to changing organisational cultures, emerging evidence and learning from the pandemic (priority).

- Evidence base (A8): Improve data quality and facilitate better understanding and use of data across the pathway by 2028, starting with (a) completing the OPD pathway data development project by 2024, to allow a better understanding of participants’ journeys on the pathway, and (b) implementing the patient outcomes database by 2024 (priority).

- Complexity of need (A1): Develop a psychologically informed action plan by 2024, in partnership with the HMPPS Public Protection Group, to set out how the OPD pathway can better engage with the imprisonment for public protection (IPP) population.

- Pathway consistency-custody (A2.2): Complete a category C commissioning plan based on stakeholder feedback and known gaps by 2024.

- Pathway consistency-custody (A2.2): Specify OPD pathway commissioning intentions for the women’s estate by 2024, informed by, for example, the Heath and Justice Women’s Review, OPD pathway data and stakeholder feedback from the strategic review.

- Diversity (A3.1): Review the OPD pathway diversity strategy by 2024 in line with the current understanding around equality and diversity, and include new workstreams to focus on intersectionality and transgender.

- Diversity (A3.1): Ensure that all OPD pathway services have a diversity action plan by 2024, to start from the 2024/25 annual business plan.

- Transitional support (A5): Identify the transitional support needs of the 18-25 male and female cohorts in the move from the youth to the adult estate by 2024, and recommend service developments informed by the evidence base, with the aim of improving stability, risk and wellbeing for this group.

- Evidence base (A8): Refresh the OPD pathway data and evaluation strategy by 2024.

Ambition and objectives for 2024-25

- Complexity of need (A1): Develop the service model in existing OPD intervention service sites to deliver an outreach service (eg ESS), where current funds allow. To have in place a plan for delivery at each site by 2025 with a view to full adoption across services by 2027 (priority).

- Pathway consistency-custody (A2.2): Create pathway progression opportunities for category C prisoners by increasing service provision, eg treatment opportunities, by 2025 (priority).

- Pathway consistency-community (A2.3): Every intensive intervention risk management service (IIRMS) to have a gender-specific offer for women, which is delivered in a women-only space, from 2025 (priority).

- Diversity (A3.1): Case formulation guidance is to be revised by the national OPD Pathway Case Formulation working group, to include recommendations that support formulations to (a) be culturally competent and (b) consider protected characteristics from an intersectional perspective, beginning with race and ethnicity. To be piloted then fully rolled out by 2025 (priority).

- Whole system response (A6): All OPD pathway commissioned services to demonstrate strong and effective joint governance arrangements between their participating agencies by 2025, which mirror those in place at national level (that is, joint NHS England and HMPPS OPD pathway programme board) (priority).

- Pathway consistency-community (A2.3): Map provision to review effectiveness of the core OPD pathway offer within the approved premises estate, to inform core guidance for the overarching OPD pathway specification, by 2025. To deliver this alongside an evaluation of approved premises psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs).

- Pathway consistency-community (A2.3): Create women’s pathway ‘WOPD enablers’ in IIRMS partnerships who will have an external-facing consultancy function. These posts will aim to support the capacity and expertise of mainstream community services for women, enabling them to work with those meeting the women’s OPD (WOPD) pathway criteria. Commissioners to explore whether this can be done within existing resources. To develop an action plan for delivery by 2025.

- Pathway consistency-community (A2.3): Commission enhanced engagement and relational support services (EERSS) by 2025, subject to evaluation, for women in the South and the Midlands regions, to ensure regional parity.

- Pathway planning (A4): Develop a communications strategy for the OPD pathway by 2025 and start implementation by 2026.

- Pathway planning (A4): Support the wider system to work with the IPP population more effectively, eg by prioritising access to services where appropriate, and offering consultancy as indicated, by 2025.

- Transitional support (A5): Confirm commissioning intentions for the provision of Pathway enhanced resettlement services (PERS) in the male and female open estate by 2024, subject to evaluation. Develop PERS guidance in response to the evaluation and population flows by 2025.

- Transitional support (A5): Evaluate provision of transitional support worker roles in WOPD pathway services and assess the feasibility of establishing this approach in the core women’s offer by 2025.

Ambition and objectives for 2025-26

- Pathway consistency-community (A2.3): Ensure equity of access to IIRMS for every probation delivery unit caseload by 2026 (priority).

- Pathway consistency-adult secure MH pathway (A2.4): Review OPD pathway medium secure units (MSUs) by 2026 with input from the NHS England Specialised Commissioning Adult Secure Mental Health team and Clinical Reference Group to ensure that the services (a) support OPD pathway outcomes, (b) are aligned with the developing structural reforms in the NHS and (c) provide a link back to standard NHS pathways of care (priority).

- Transitional support (A5): Support the IIRMS network and relevant community and prison partners to improve the quality and frequency of IIRMS in-reach, informing associated guidance, by 2026 (priority).

- Pathway consistency-national (A2.1): Develop a shared understanding of the full pathway and governance requirements for medication to manage sexual arousal (MMSA) services in custody and community by 2026, working in partnership with NHS England Health and Justice.

- Pathway consistency-community (A2.3): Ensure that core and IIRMS services work together to offer a seamless experience to people on probation by 2026, using the new OPD pathway single specification and guidance documentation.

- Diversity (A3.1): Review the applicability of the OPD pathway screening tools to the 18-25 male and female young adult cohort by 2026.

- Pathway planning (A4): Work with probation to develop a quality assurance process to oversee the core offender management service by 2026.

- Pathway planning (A4): Provide fit for purpose case management processes by 2026 for complex women who satisfy the criteria for the OPD Pathway but who are not included in the Women’s Estate Case Advice and Support Panel caseload.

- Pathway planning (A4): OPD pathway services to develop a digital information pack by 2026, including the lived experience perspective, to support people to access the most appropriate service for their needs.

- Relational practice culture (A7): Enhance the quality of OPD pathway services by embedding the OPD pathway quality standards framework into service-level business plans by 2025. Support this further with the development and piloting of a co-produced peer-review process by 2026.

- Relational practice culture (A7): Promote and develop the quality of formal and informal support and reflective spaces provided for OPD pathway staff, to meet the expectations of the quality standards framework, by 2026.

- Evidence base (A8): Establish an OPD pathway evaluation network and online platform by 2026, that encourages collaboration, shares good practice and facilitates high quality service evaluations.

Ambitions and objectives for 2026-27

- Pathway consistency-national (A2.1): Transition all OPD pathway commissioned services onto an outcomes-focused overarching service specification for the national OPD pathway, by 2027 (priority).

- Transitional support (A5): Establish a transitions task and finish group that develops guidance and expectations around management of pathway transitions by 2027, considering application of relevant quality standards and specifications (priority).

- Complexity of need (A1): Develop psychologically informed guidance for staff working with those the OPD pathway has not yet reached, particularly prisoners in local and reception prisons, category C prisoners and those in segregation units, ensuring this is co-produced with other key stakeholders, by 2027.

- Pathway consistency-national (A2.1): To support the OPD pathway single specification, develop a suite of service and thematic guidance, collaboratively and with the involvement of service participants, and considering issues of intersectionality, by 2027.

- Pathway consistency-custody (A2.2): Align all legacy dangerous and severe personality disorder (DSPD) services with the OPD pathway overarching specification, contracting and commissioning intentions by 2027.

- Pathway consistency-adult secure MH pathway (A2.4): The overarching OPD pathway specification and guidance documents will (a) set out the OPD pathway MSU provision offer to determine the optimum service offer in those locations and (b) ensure the OPD pathway MSUs link to the care pathways set out in the other adult secure specifications, by 2027.

- Transitional support (A5): Explore the use and impact of existing progression support roles in men’s OPD pathway services and assess the feasibility of extending this way of working across men’s services by 2027.

- Transitional support (A5): Work with the HMPPS Community Accommodation Service to successfully implement and deliver the PIPE model in approved premises in existing identified sites in England and complete an evaluation of these services, by 2027.

- Transitional support (A5): Develop an OPD pathway accommodation strategy by 2027 in conjunction with relevant stakeholders and taking account of existing services, evaluations and proposed pilots, to improve the housing options for OPD Pathway participants.

- Relational practice culture (A7): Support OPD pathway services to work towards the enabling environments standards by 2027, and work with the Royal College of Psychiatrists to develop the enabling environments network.

- Relational practice culture (A7): Explore the benefits to custodial services providing whole wing staff training in therapeutic approaches by 2027, with a view to further piloting.

- Evidence base (A8): Improve evidence-informed practice, sharing data findings, recommendations and the wider evidence base, via accessible sources, such as data visualisations and first look evidence summaries, by 2027.

Ambitions and objectives 2027-28

- Pathway planning (A4): Integrate the OPD pathway and a psychologically informed approach with offender management processes by 2028, by working collaboratively with the relevant teams in probation (priority).

- Whole system response (A6): Create opportunities over the next 5 years to contribute to training and development for those working within OPD pathway host organisations, eg entry level training, leadership training (priority).

- Evidence base (A8): Complete in-house and commissioned evaluations on the priority areas identified in the data and evaluation strategy, focusing on effectiveness, by 2028 (priority).

- Complexity of need (A1): Optimise the OPD core offender management (core OM) intervention for those highly complex individuals the pathway has not yet reached, using the quality standards framework, by 2028.

- Pathway consistency-national (A2.1): With key stakeholders, explore opportunities over the course of this strategy for jointly commissioned initiatives to improve consistency of service provision across the stakeholder landscape.

- Pathway consistency-custody (A2.2): Assess the impact of future population flows, need and new prison builds to inform future commissioning intentions. To be completed over the course of this strategy.

- Diversity (A3.1): The national OPD pathway team to provide structured opportunities over the course of this strategy for the OPD pathway workforce to meet and establish systems to embed diversity and inclusion.

- Diversity (A3.1): Seek opportunities over the course of this strategy to improve equitable access to OPD pathway services for those with physical disabilities and sensory impairment by linking in with HMPPS and NHS estate improvement programmes.

- Diversity (A3.1): OPD pathway co-commissioners to (a) work with existing services to plan how services can accept people with physical disabilities or sensory impairment, and (b) when commissioning new services, to explicitly consider whether the site is able to make reasonable adjustments to accommodate those with physical disabilities or sensory impairment.

- Inclusion (A3.2): Deliver workstreams for substance misuse, neurodiversity and mental health/illness that will explore the interdependencies and relevant evidence base, and make recommendations for both the men’s and women’s pathways. To be completed by 2028 and to start with substance misuse.

- Inclusion (A3.2): OPD pathway co-commissioners to (a) work with existing services to plan how the service can accept people with an index sexual offence and (b) when commissioning new services, to explicitly consider whether the site would accept people with an index sexual offence.

- Whole system response (A6): Continue to expand the target audience for (awareness level) KUF and women’s KUF (W-KUF) over the course of this strategy to staff groups working with likely ‘personality disorder’ outside OPD pathway services.

- Whole system response (A6): Use psychologically informed consultancy, supervision and training to support those working in non-statutory agencies to work more effectively with those with likely ‘personality disorder’ by 2028.

- Whole system response (A6): Seek opportunities to embed OPD pathway principles and practice over the course of this strategy by engaging with high-level strategic organisational change, eg integrated care systems, future regime design and probation unification.

- Relational practice culture (A7): Support and work with academic, clinical and lived experience colleagues, eg the British and Irish Group for the Study of ‘Personality Disorder’ community of practice, over the course of this strategy, to further develop the evidence base around relational practice.

- Relational practice culture (A7): Continue to fund academic work to ensure OPD pathway practice is based on developing knowledge in this field and that the pathway develops informed leadership that recognises relational principles and practice.

- Evidence base (A8): Continue to develop external partnerships over the course of this strategy, collaborating with academics and third parties to seek more funding opportunities.

- Evidence base (A8): Undertake a series of additional, large-scale evaluations over the course of this strategy, in line with the priorities identified in the data and evaluation strategy.

2. Future developments subject to resourcing

Ambition and future objectives subject to resourcing

- Complexity of need (A1): Draw up proposals for expansion of the ESS delivery model into prisons outside the existing OPD pathway footprint, for submission through the next spending review framework (expected by 2026).

- Pathway consistency-community (A2.3): Develop a business case by 2026, either for spending review or underspend resources, to pilot an ESS in the community model, based on a multidisciplinary team, eg social workers and housing officers.

- Pathway consistency-community (A2.3): Design and pilot different service models to deliver a positive housing outcome for those who meet screening criteria, by 2026, building on existing expertise and including an embedded evaluation. Develop a business case (subject to evaluation) for submission through the next spending review framework.

References

- Richardson J, Zini V (2021) Are prison-based therapeutic communities effective? Challenges and considerations. International Journal of Prisoner Health 17(1): 42-53.

- Knauer V, Walker J, Roberts A (2017) Offender personality disorder pathway: The impact of case consultation and formulation with probation staff. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 28(6): 825-840.

- Blinkhorn V, Petalas M, Walton M, Carlisle J, McGuire F (2020) Understanding offender managers’ views and experiences of psychological consultations. European Journal of Probation 13(2): 95-110.

- Wheable V, Davies J (2020) Examining the evidence base for forensic case formulation: An integrative review of recent research. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 19(3): 315-328.

- Wheable V, Lewis C, Davies J (2022). Investigating the effectiveness of forensic case formulation recommendations. Psychology, Crime & Law 1-19.

- Shaw J, Higgins C, Quartey C (2017) The impact of collaborative case formulation with high risk offenders with personality disorder. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 28(6): 777-789.

- Minoudis P, Craissati J, Shaw J, McMurran M, Freestone M, Chuan SJ, Leonard A (2013) An evaluation of case formulation training and consultation with probation officers. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 23(4): 252-262.

- Shaw J, Minoudis P, Hamilton V, Craissati J (2012) An investigation into competency for working with personality disorder and team climate in the probation service. Probation Journal 59(1): 39-48.

- Moran P, et al (2022) National Evaluation of the Male Offender Personality Disorder Pathway Programme.

- Reading L, Ross GE (2020) Comparing social climate across therapeutically distinct prison wings. The Journal of Forensic Practice 22(3): 185-197.

- Turley C, Payne C, Webster S (2013) Enabling features of psychologically informed planned environments. Ministry of Justice Analytical Series.

- Hadden JM, Thomas S, Jellicoe-Jones L, Marsh Z (2016) An exploration of staff and prisoner experiences of a newly commissioned personality disorder service within a category B male establishment. Journal of Forensic Practice 18(3): 216-228.

- Kuester L, Freestone M, Seewald K, Rathbone R, Bhui K (2022) Evaluation of Psychologically Informed Planned Environments (PIPEs). Assessing the first five years.

- Camp J, Joy K, Freestone M (2018) Does “enhanced support” for offenders effectively reduce custodial violence and disruption? An evaluation of the enhanced support service pilot. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 62(12): 3928-3946.

- Nathan R, Centifanti L, Baker V, Hill J (2019) A pilot randomised controlled trial of a programme of psychosocial interventions (Resettle) for high-risk personality disordered offenders. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 66: 101463.

- Shaw J, Higgins C, Quartey C (2017) The impact of collaborative case formulation with high risk offenders with personality disorder. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 28(6): 777-789.

- Ryan S, Eldridge A, Duffy C, Crawley E, O’Brien C (2022). Resettle intensive intervention and risk management service (IIRMS): a pathway to desistence? The Journal of Forensic Practice 24(4): 264-375.

- Bruce M, Crowley S, Jeffcote N, Coulston B (2014) Community dangerous and severe personality disorder pilot services in South London: Rates of reconviction and impact of supported housing on reducing recidivism. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 24: 129–140.

Publication reference: PRN00321