Introduction

Virtual wards allow patients of all ages to safely and conveniently receive acute care at their usual place of residence, including care homes.

There is growing evidence that when all core components of these services are delivered at scale for appropriate patients, they provide a better patient experience and can improve outcomes compared to inpatient care, and narrow the gap between demand and capacity for hospital beds by preventing attendances and admissions, shifting acute care into the community or reducing length of stay through early discharge. The virtual ward model has broad clinical support, including endorsement from professional bodies.

Virtual wards are now available in every integrated care system (ICS), although there is variation in the models and pathways they deliver. This is due to pre-existing service arrangements to address local need, and because national policy has supported a diversity of approaches to enable rapid expansion. Some local variation will remain appropriate; however, evaluation suggests that greater consistency nationally in the components of virtual wards would maximise benefits for patients and the wider system. Feedback also suggests that clinicians across the country are keen to better understand where this expansion has been most successful, to inform development of best practice models.

This framework supports consistency across the NHS and the relevant goals in line with the Year 2 urgent and emergency care (UEC) recovery plan and the 2024/25 priorities and operational planning guidance: maintaining virtual ward capacity and optimising occupancy so it is consistently above 80%. It also clarifies the expectations of virtual wards and how they should be developed over time to maximise benefits for patients and the NHS, by setting out:

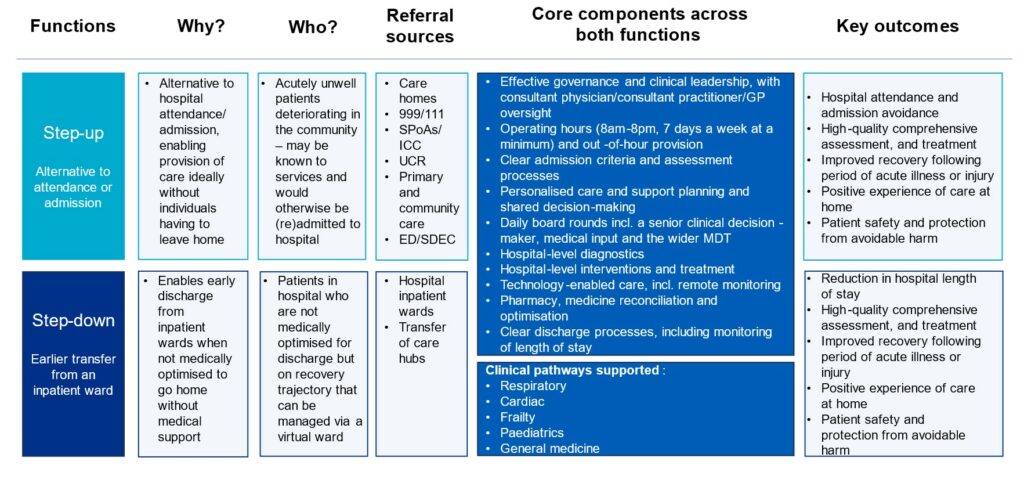

- what virtual wards are and do, including step-up and step-down functions

- the core components of a ‘good’ technology-enabled virtual ward

- requirements for implementation and alignment with key partners

- the expected outcomes of virtual wards, including ensuring capacity is aligned with avoiding hospital attendances and admissions and/or reducing length of stay in inpatient wards

The framework has been developed in conjunction with the National Clinical Advisory Group, the Virtual Wards Steering Group and voluntary sector partners. It is intended for everyone involved in the planning, implementation, delivery and/or monitoring and evaluation of virtual wards, including providers and integrated care boards (ICBs).

As this framework updates two pieces of previously published guidance – ‘Supporting information for ICS leads – enablers for success: virtual wards including hospital at home’ and ‘Supporting information: virtual ward including hospital at home’, these documents have been withdrawn. We have published additional guidance specifically for acute respiratory illness, frailty and heart failure pathways. Other virtual ward pathways should be developed at a local level to meet population needs, including for children and young people (CYP) – see appendices 1 and 4.

Benefits of virtual wards

The virtual ward model has broad clinical support, including endorsement from professional bodies, and is underpinned by a growing evidence base that demonstrates patient, system and staff benefits when all core components are delivered at scale for appropriate patients.

Preventing admissions and attendances

Virtual ward models reduce hospital admissions and readmissions with knock-on impacts for emergency department (ED) presentations through the provision of timely consultant-led* multidisciplinary care (NHS England, 2024; Wessex Academic Health Science Network, 2022). This is not only the case for frailty models but also CYP virtual wards, with data from Providing Assessment and Treatment for Children at Home (PATCH) in Hillingdon showing significantly reduced admissions to the paediatric assessment unit after implementation (Health Innovation Network South London, 2024).

* Consultant includes consultant physicians (surgeons, geriatricians, paediatricians), consultant practitioners (nurses, allied health professionals with consultant-level practice) and GPs (including GPs with extended roles). It does not include advanced practitioners.

South East evaluation: A 2023/24 evaluation of over 22,000 virtual ward admissions to step-up/admissions avoidance pathways across 29 sites found that 2.5 virtual ward admissions are associated with 1 fewer non-elective admission – equating, for these services alone, to over 9,000 avoided hospital admissions a year across the region. The most mature services can achieve a ratio of nearly 1:1.

Kent Community Health NHS Foundation Trust (KCHFT): The frailty HaH service at KCHFT covers an area with a large population living with frailty, with over 6,000 residents in 275 care homes. Over the course of 2 years while the HaH service has continued to expand, medical hospital admissions and attendances of people over 75 have reduced by 25%.

Reduced hospital length of stay

Step-down virtual ward models reduce length of stay for specific cohorts (for example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure) (Eastern AHSN and Health Innovation Manchester, 2023; Chauhan U, McAlister FA, 2022).

Cost-effectiveness and productivity

The South East evaluation found that the annualised net benefit was £10.4 million for the 18 pathways analysed for non-elective admissions (and this does not include all virtual ward activity in the region). Local evaluations have also demonstrated cost savings (with these greatest for step-up functions (Wessex Academic Health Science Network, 2022)) from delivering care in people’s homes with one report citing an average cost saving of £1,958 per patient compared to an inpatient stay in the UK, as well as productivity and efficiency savings through use of technology including remote monitoring (Health Innovation Network South London, 2024).

North West London (NWL) Virtual Hospital: From April 2022 to April 2023, 4,311 patients were managed through NWL virtual ward pathways with an estimated 8,622 bed days saved and a £3,448,800 system saving. Technology is a key enabler for virtual ward pathways and 84% of these NWL virtual ward patients received technology-enabled care.

Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust: The Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust HaH services used a simple modelling approach, Demand and Capacity ‘lite’, to understand how additional investment in the multiprofessional team increases capacity and number of HaH ‘beds’. Their approach was useful to explore funding scenarios and understand how investment could increase patient-facing time.

Improved patient experience and choice

Feedback from patients is positive (Nunan J, et al 2022; Chen H, et al, 2024) and suggests that virtual wards support increased patient choice and personalised care as well as providing opportunities for family members to visit and engage with patients (Chua CMS, et al, 2022).

Improved patient outcomes and protection from avoidable harm

Outcomes for patients in a virtual ward are comparable to or better than those in inpatient care, including mortality and readmissions (Leong MQ, et al. 2021; Norman G, et al, 2023). Frailty virtual wards reduce the risk of deconditioning and loss of independence associated with an emergency conveyance and admission to hospital, with these benefits greatest for admission alternative service models (Shepperd S, et al, 2021). By supporting individuals to stay out of hospital, virtual wards can also reduce the risk of hospital-acquired infections (Chappell P, et al, 2024).

Leeds, West Yorkshire Integrated Care Board: Pharmacy input for the frailty virtual ward in Leeds has been instrumental in optimising medicines outcomes for patients and improving patient experience. Having pharmacy staff embedded at all levels of leadership ensures pharmacy professionals are collaborators in developing pathways, mitigating medicine-related risks and influencing future developments of the frailty virtual ward.

Improved staff experience

Virtual wards improve staff experience and retention (Health Innovation Network South London, 2024; Schultz K et al, 2021), and create opportunities for staff to undertake flexible and blended roles.

What is and is not a virtual ward?

A virtual ward is an acute clinical service with staff, equipment, technologies, medication and skills usually provided in hospitals delivered to selected people in their usual place of residence, including care homes. It is a substitute for acute inpatient hospital care. This definition is based on the World Hospital at Home Congress consensus definition (2023).

Virtual ward services are fully responsible for the patient, providing medical, nursing and allied healthcare support through a multidisciplinary team (MDT). The support provided by the MDT may be delivered by several different teams working to deliver the virtual ward service.

A virtual ward is defined by:

- effective governance and clinical leadership, with consultant physician/consultant practitioner/GP oversight

- operating hours (8am–8pm, 7 days a week at a minimum) and out-of-hours provision

- clear admission criteria and assessment processes

- personalised care and support planning and shared decision-making

- daily board rounds involving a senior clinical decision-maker, medical input and the wider MDT

- hospital-level diagnostics

- hospital-level interventions/treatment

- technology-enabled care, including remote monitoring

- pharmacy, medicine reconciliation and optimisation

- clear discharge processes, including monitoring of length of stay

A virtual ward is suitable for a range of acute conditions, including but not limited to respiratory problems, heart failure or exacerbations of a frailty-related condition for adults, and acute respiratory illness, gastroenteritis and neonatal jaundice for CYP. The case mix may range from patients who primarily require daily monitoring virtually or by phone and reviews to those who require multiple home visits within a day from a member of the MDT. The length of stay can be different for each person but is expected to be short (up to 14 days).

The acuity of the patients differentiates virtual wards from other community services and should be high enough to warrant consultant physician/consultant practitioner/GP oversight, with clear lines of clinical governance and accountability in place as outlined in the Supporting clinical leadership in virtual wards guidance.

A virtual ward is not a mechanism intended for:

- routine GP-led medical and urgent care

- proactive deterioration prevention

- standalone remote monitoring or virtual care

- safety-netting, for example when patients are medically optimised for hospital discharge/do not require acute care but their symptoms may change

- intermediate care and reablement

- a bridging care service for patients awaiting a care package

- standalone outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT)

- standalone home-based end-of-life (EoL) care (although virtual wards may frequently refer patients to these services on discharge)

- standalone home intravenous or infusion therapy

Although in practice some of the above functions/services may be delivered by the same staff as those working on virtual wards, or may overlap with the provision of virtual ward care for some patients, on their own they do not meet the definition of what a virtual ward is. For example, standalone OPAT services are not virtual wards but can be an enabler of virtual ward treatment as part of an MDT. Patients receiving OPAT are often not as acutely unwell as those admitted to a virtual ward, and their treatment may extend over a long time.

Assessing acuity

While no one method is consistently used to measure acuity in virtual wards, services should take steps to understand the level of acuity of the patients they support to maximise benefits for patients and system flow. The National Early Warning Score version 2 (NEWS2) for adults and the Paediatric Early Warning System (PEWS) for CYP are considered important, if not definitive, tools for identifying acutely ill patients who might be suitable for virtual ward care. Various providers are also developing their own tools to assess acuity based on interventions, the professionals involved, scoring systems and patient conditions.

Where a patient is referred from an inpatient ward, services may look at using clinical criteria to reside as another way to determine the suitability of a patient for a virtual ward.

What good looks like

Core functions and components of virtual wards

Virtual wards serve 2 core functions:

- ‘step-up’ care is where a patient becomes acutely unwell and is offered the choice between being treated at home or in hospital. Patients are typically referred directly from their usual place of residence and can be admitted from sources such as a single point of access (SPoA), same day emergency care (SDEC) or ED

- ‘step-down’ care is where a virtual ward can facilitate an earlier discharge or transfer from an inpatient ward, enabling individuals who are not medically optimised for discharge to continue to receive medical treatment, oversight and diagnostics at home

Surrey Downs Health and Care Partnership (SDHCP): The Integrated HomeFirst Service at SDHCP provides health and social care support to people in their homes as an alternative to a hospital admission or an extended acute stay. HomeFirst incorporates a virtual ward, urgent community response (UCR), Discharge to Assess (D2A) and a transfer care hub. By working together with a ‘one team’ ethos, the different services provide joined-up care across traditional boundaries and ensure both step-up and step-down referrals are made into the virtual ward.

Figure 1: Overview of virtual wards, including functions, core components and key outcomes

Providers should work towards ensuring all virtual wards deliver all of the core service components listed in Table 1. At a minimum, providers should ensure closer alignment of both step-up and step-down functions, and consider opportunities for integration and economies of scale when delivering the core components, which may require joint working between acute and community providers (for example, where providers may need specialist medical input from a neighbouring provider). This will increase the flexibility to match capacity and capability to fluctuations in patient needs and demand.

West Hertfordshire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust: The virtual hospital in West Hertfordshire is a system-wide collaborative project across primary, community, acute and the voluntary sectors that supports both step-up and step-down functions. Acting as a generic frailty model, patients are referred from a variety of services as well as case finding and then onboarded by the Virtual Hospital Hub. Patients can then receive the specialist care required for their condition (for example, cardiology, respiratory, frailty and pharmacy). In most situations, this involves the acute trust having respiratory and cardiology consultant-level virtual ward leads who have dedicated time (for example, 1 programmed activity weekly) to plan and deliver this activity in the context of an integrated MDT.

City Healthcare Partnership Community Interest Company (CIC), Hull and East Riding: This CIC provides a joined-up frailty virtual ward and urgent community response (UCR) service that uses a range of point of care testing, physiological measurement and imaging devices, and has access to wider diagnostics to support rapid clinical decision-making and patient management.

North Cumbria Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust: British Red Cross holistic support workers are an integral part of the trust’s HaH service. They address health inequalities by improving access to the service from a wider cohort of patients and improving their experience. Support workers attend daily board rounds as part of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) and undertake holistic assessment of patients to identify and meet any wider needs that might impact on patients’ health outcomes and experience, including digital and health literacy, daily living needs and the safety of the home environment.

Table 1: Core service components for providers delivering virtual wards

| Core components | Key requirements and considerations for implementation |

|---|---|

| Effective governance and clinical leadership, with consultant physician/consultant practitioner/GP oversight | Virtual wards should have clear lines of clinical responsibility and effective and safe governance, with consultant physician/consultant practitioner/GP oversight for all patients, as outlined in the Supporting clinical leadership in virtual wards guidance. See appendix 2 for additional information on legal requirements. The named consultant physician/consultant practitioner/GP for the virtual ward, which could be a doctor (including a medical consultant or a GP with an extended role), nurse or allied health professional (AHP) with consultant-level practice and knowledge and capabilities in the relevant specialty or care model, holds accountability for all patients admitted to the virtual ward. Where a patient is admitted from an inpatient ward, the accountability should be transferred before the patient leaves hospital unless the accountable clinician is the same individual in both care settings. The accountable clinician for the virtual ward may be the same person as the senior clinical decision-maker responsible for daily activities including board rounds, but this does not have to be the case. Patients should be monitored to support early recognition of deterioration and appropriate escalation processes should be in place to maintain patient safety. Training on escalation processes should be provided to carers and staff as necessary Virtual wards should have processes in place to monitor clinical safety and incident reporting. This should capture learning on clinical safety, including digital clinical safety across service partners, with a route into system clinical governance. There should be regular monitoring of patient morbidity and mortality for the virtual ward, which should include reviews of clinical incidents and complaints. Services should ensure patients and/or their carers are given information on who to contact if symptoms worsen, including out of hours. Information should adhere to the Accessible Information Standard. |

| Operating hours (8am-8pm, 7 days a week at a minimum) and out-of-hour provision | Virtual wards should ensure staffing for a minimum of 12 hours a day (8am-8pm), 7 days a week, with locally arranged provisions for out-of-hours cover and access to specialty advice and guidance as required. Operating procedures should be in place to ensure support is available out of hours to manage deterioration and maintain patient safety 24 hours a day. In many cases this will involve integration of a virtual ward with existing interfaces (for example, GP out-of-hours services, community nursing, urgent community response (UCR) and NHS 111). Virtual wards should ensure that processes are in place for patients to access out-of-hours services and that it is clear what support these services are able to provide to enable a seamless transition of care for the patient. Virtual wards should continually review out-of-hours contracts to support any additional service demand that might emerge. This is particularly important when proactively identifying step-up demand that could be diverted from inpatient care. |

| Clear admission criteria and assessment processes | For all admissions to a virtual ward, a senior clinical decision-maker, under the oversight of a consultant physician/consultant practitioner/GP, should promptly assess patients to decide whether they should be admitted to a virtual ward. This may be in consultation with other specialty clinicians. Assessment may include comprehensive geriatric assessment where indicated, calculation of NEWS2 score, Clinical Frailty Score (CFS) screening and 4AT rapid test for delirium in adults. These assessments may help risk stratify the appropriateness of virtual ward care but should not be used on their own to exclude a person from admission to a virtual ward. Paediatric early warning system (PEWS) could be used to support admission decisions for children and young people. Admission criteria should reflect the acuity of virtual ward patients, and there should be policies in place to ensure equity of access in the admission and assessment processes and reduce health inequalities. For patients transferring to a virtual ward from an inpatient ward (known in virtual ward terms as a ‘step-down pathway’, although patients will still require hospital-level care), hospital staff should proactively identify suitable patients, including during their twice daily ward rounds at a minimum. They should work with transfer of care hubs to support discharge to virtual ward care, in line with the Hospital discharge and community support guidance. The decision to admit a patient to a virtual ward will be made in conjunction with the senior clinical decision-maker in the virtual ward. Recognising when an individual might be in their final days or weeks of life can be a key role of a virtual ward. Appropriate assessment should occur in line with the Gold standard framework. An assessment of a patient’s holistic needs should be undertaken – or have been undertaken by/jointly with a transfer of care hub for patients transferring from an inpatient ward – to ensure that virtual ward care is adapted to the individual patient’s circumstances and their wider needs. Holistic needs assessments should include a home environmental assessment, a falls risk assessment and a safeguarding assessment. An assessment of the needs of a patient’s carer should also be undertaken to ensure they are properly supported, for example by reference to the carers’ checklist |

| Personalised care and support planning and shared decision-making | Services should provide patients (and/or their carers) with adequate information to ensure informed consent for treatment on a virtual ward and make any reasonable adjustments required. If an individual lacks capacity to make informed consent, then their representative or a best interests assessor should be involved to advocate on behalf of the individual’s interests and needs. There must be a documented shared decision-making process with patients and/or carers consenting to admission with full awareness of the benefits and risks. This includes delivery of care in their home environment and carers’ circumstances. Personalised interventions, including co-produced care and support plans, should be agreed. Advance care planning conversations should occur to ensure what matters to patients is documented in a place that all staff can access and these advance care plans are respected in the event of patient deterioration. Care should otherwise reflect of any previously agreed advance care plan |

| Daily board rounds involving a senior clinical decision-maker, medical input and the wider MDT | Board rounds should be overseen by a senior clinical decision-maker, occur daily, include medical input and be supported by a dedicated multidisciplinary team (MDT) encompassing a variety of disciplines as would be the case in a hospital (that is, consultant physicians/GPs, physicians, registered nurses, AHPs, advanced clinical practitioners, pharmacists). The MDT should include other relevant professionals when required, including social care teams, mental health and voluntary sector organisations. When tasks are delegated to non-NHS staff, including social care, local services should ensure sufficient funding arrangements are in place. A record of interventions and treatments should be accessible to all appropriate professionals involved in a patient’s care |

| Hospital-level diagnostics | All virtual wards should ensure patients have access to tests and urgent diagnostics as they would in a hospital (for example, blood tests, CT scan, X-ray and MRI) to allow for responsive and timely decision-making, in line with national guidance on access to diagnostics on virtual wards. When setting up pathways to access tests and urgent diagnostics, services should work closely with local pathology networks to ensure appropriate clinical governance, and to avoid hospital admissions for the sole reason of accessing a test. Virtual wards may partner with care settings such as SDEC and community diagnostics centres, and should work with ICB transport leads to ensure patients can access transport to and from these settings as required. They should also consider how samples taken at home will be transported to the laboratory. Virtual ward staff kit bags should include portable medical devices, such as in vitro point of care testing and point of care ultrasound devices, to enhance assessments and accelerate clinical decision-making |

| Hospital-level interventions/treatment | Virtual wards should offer in-person visits to a patient’s usual place of residence in conjunction with care management and monitoring, which can be technology-enabled. There should be access to advice and guidance from other specialists, consultant-level reviews and medicines management and optimisation. Appropriate in-person therapies should be available, such as intravenous and subcutaneous fluids, intravenous diuretics, therapy, nebulisers and oxygen. The MDT may also provide at home services, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, assessment and delivery of equipment to improve independence and reduce risk of harm |

| Technology-enabled care, including remote monitoring | All virtual wards should have the capability and capacity to use technology-enabled monitoring, where appropriate, to improve access to information that supports clinical decision-making, and support remote consultation and connections between the patient and their care team. Technology should not be used to deliver virtual care where face-to-face care is required. Services should be able to support patients, carers and care home staff with the use of technology and offer alternatives to prevent digital exclusion. Electronic patient record (EPR) configuration should support delivery of virtual wards by enabling access to information across all delivery partners. This should also provide read/write functionality and enable the flow of clinical information from referral, assessment, admission, care delivery (including visibility of remote monitoring data) and discharge or ongoing transfer of care. Where electronic prescribing and medicine administration (ePMA) and e-prescribing systems are not integrated with provider EPRs, these should be optimised to reduce the risks of medical error; support process improvement; and enable integration across service partners |

| Pharmacy, medicine reconciliation and optimisation | There should be equitable access to pharmacy, with dedicated pharmacy professionals involved in daily board rounds and MDT meetings as required, and in the delivery of comprehensive assessments. Virtual wards, particularly their step-up functions, should have access to medicine ‘grab bags’ to ensure timely access to appropriate treatments. Processes for prescribing and deprescribing, dispensing and delivering medicines should be clearly defined and signed off by the organisation’s chief pharmacist or equivalent. Where possible, medicines should either be delivered to the patient’s usual place of residence or e-prescribing used to dispense medicines to a local pharmacy to limit travel. On discharge from a virtual ward, relevant information about changes to a patient’s medicines should be shared with the patient’s GP and community pharmacy. This could be shared via a summary care record |

| Clear discharge processes, including monitoring of length of stay (up to 14 days) | Virtual wards should agree the estimated discharge date for a patient on admission based on clinical judgement and in discussion with the patient and/or their carer. Patients should be discussed daily to identify whether they still require acute care or should be discharged. Decisions should support the safe and timely discharge of people in line with the Hospital discharge and community support guidance. The length of stay can differ for each person, but is expected to be short (especially where a virtual ward admission for diagnostics and rapid treatment replaces an ED attendance) and up to 14 days. Services should monitor length of stay to ensure it is appropriate for both patients’ needs and local demand and capacity considerationsServices should ensure early discharge planning, including early referral to transfer of care hubs for anyone likely to require an additional package of support on discharge. Suitable arrangements should be made for transferring care from the virtual ward to alternative pathways, including those led by primary, community or social care. This includes rehabilitation and reablement services as outlined in the Intermediate care framework for rehabilitation, reablement and recovery following hospital discharge; long-term condition management services (including NHS @home services); and EoL and specialist palliative care services. There should be appropriate communication with patients and carers to ensure they understand the discharge process and are aware of onward referrals or required further management by other services |

Devon Integrated Care System: The virtual ward in Devon conducted a pilot to reduce potential health inequalities associated with virtual wards; further develop their relationship with the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector; and improve the experience of patients and their carers. As a result, patients were able to get the support they needed to use digital equipment, which had a positive impact on clinical capacity and reduced the need to bring patients back to the hospital for digital support.

Operational and implementation requirements for integrated care boards

All ICBs should consider the best practice activities in Table 2 and collaborate with relevant services and partners across their system to support their delivery. This includes improving access to virtual wards and use, with a focus on frailty, acute respiratory illness, heart failure and CYP.

Table 2: ICB requirements for implementation

| 1. Lead and co-ordinate strategic oversight and planning | |

| 1a. Dedicated leadership | Good practice suggests having ICB leadership (that is, an executive lead, clinical leads and UEC operational lead) in place to provide appropriate governance and risk management of the delivery of virtual wards at a system level, as well as ensure that there is oversight of the growth, quality and use of virtual wards alongside wider UEC and system management. |

| 1b. Capacity and demand planning and management | To maximise the impact of virtual wards, virtual ward capacity should be strategically co-ordinated and delivered at a place and system level alongside existing out-of-hospital and physical hospital capacity, ensuring it is used as efficiently and productively as possible. Having a capacity and demand plan for virtual wards across the ICS can be useful, one that considers both CYP and adults and prioritises key UEC demands as well as suitable discharge arrangements including links with social care. This plan can then link into other system capacity and demand plans, including for all out-of-hospital services at ICB level in addition to Better Care Fund plans. ICBs should consider how to support the flow of operational data, including real-time capacity, to ensure accurate occupancy data is available as part of provider capacity and UEC capacity management across the system. |

| 1c. Digital transformation and use of data and technology | Good practice suggests virtual wards and their unique requirements are considered as part of wider ICB digital strategies, addressing any variability in digital maturity across all service providers, based on the What Good Looks Like framework. The use of digital technologies (for example, medical devices, diagnostic equipment, remote monitoring equipment) can enhance the efficiency of virtual wards as part of system-wide approaches to achieve economies of scale (see the Digital clinical safety strategy). ICBs should consider how to enable effective access to care information across service partners, including transfer of information from remote monitoring devices and remote diagnostic test results (including imaging), allowing patient information to be recorded remotely and supporting interoperability of EPR systems. Improved data quality and access to operational data support wider UEC system capacity management. |

| 2. Lead on alignment of referral pathways and improving system flow | |

| 2a. Referrals and flow | ICBs, providers, services and all relevant system partners should work together locally to improve the flow of referrals to virtual wards. This includes supporting providers to educate and support case finders and referrers, such as NHS 111, 999, primary care, community care, care homes, acute respiratory infection hubs, transfer of care hubs, inpatient settings, the voluntary sector and social care. ICBs are responsible for ensuring population and live maintenance of the information in the Directory of Services to support safe and effective referrals into virtual wards, which may require regional input to support consistency. |

| 2b. Streamlining access to step-up virtual wards | ICBs could consider the operational alignment of virtual wards with UEC to support the development and expansion of virtual wards that provide an alternative to hospital attendance or admission, particularly when accessed directly from home. Where possible, ICBs should encourage utilisation of a single point of access (SPoA) or an integrated care co-ordination (ICC) centre to maximise the use of virtual wards along with other services across a system (for example, UCR, respiratory infection hubs, SDEC, acute frailty and falls services). Good practice suggests that integrating or aligning UCR and virtual ward services can support a pathway approach and the sharing of resources. |

| 3. Lead on ensuring equitable and sustainable service provision across a system | |

| 3a. Reducing unwarranted variation | ICBs are uniquely placed to develop a consistent offer of virtual wards and pathways across the system, in line with the functions and core components outlined in this framework. This includes implementing consistent ICS-wide admission and discharge criteria. ICBs could consider provider collaboratives to deliver virtual wards across community, secondary and primary care. |

| Health inequalities measures should be embedded to enable equitable virtual ward access, experience and outcomes across different population groups with protected characteristics, including age, sex, race or membership of a health inclusion group. | |

| 3b. ICB funding and long-term planning | The funding of virtual wards should be reflected in ICB planning to ensure their sustainability, with virtual wards built into ICB long-term strategies and expenditure plans. |

| 4. Lead on supporting workforce planning and capability with providers and places | |

| 4a. Supporting workforce capacity and capability | Workforce capacity and productivity can be supported by enabling providers to share staff flexibly across services as required (for example, through sharing agreements and ‘passport’ arrangements). In some instances, planning and investment will be needed to ensure the right specialist care can be provided across the system. ICBs can support providers to match workforce capacity to demand, following the principles of safe, sustainable and productive staffing. This should follow National Quality Board guidance on safe staffing with a triangulated approach using evidence based tools, professional judgement, comparison with peers and monitoring alongside clinical outcomes. |

| ICBs should explore how training provision (for example, advanced clinical practice courses and training on remote clinical assessment) and opportunities can be shared across providers to support staff to develop the skills and competencies outlined in the Capabilities framework, to accompany the eLearning on the Learning Hub. | |

| Developing partnerships within local communities, including with the independent sector and other local organisations, has proven to support the capability building, particularly to ensure a diverse skill mix is available to meet holistic needs. This includes partnerships with the local authority, social care, care homes and others across the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector. ICBs can explore the development of plans to enable training and career routes through virtual wards, to support staff recruitment to and retention in virtual wards in line with the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan. | |

Data, outcomes and metrics

As systems expand virtual wards, robust and consistent data is needed to assess progress in scaling services and build evidence about their effectiveness. Data should be systemically gathered on clinical effectiveness, patient safety, patient and carer experience, staff experience and resource use for virtual wards.

The ambition is to automate the flow of a new Minimum Data Set (MDS) via the Federated Data Platform (FDP), which will provide daily operational data providers and systems require as well as data for secondary use and evaluation. Data will continue to be collected via the Virtual Wards Situation Report until providers supply a patient-level flow via the FDP and the Faster Data Flows Programme.

A set of recommended virtual ward indicators and outcomes that aligns with the MDS are listed in Table 3, and should be used by service providers and ICBs to develop an understanding of the activity and impact of their virtual wards. Evaluation and research show that outcome metrics are more likely to be achieved where services are mature and delivered at scale and in line with the core components in Table 2 above and the operational metrics in Table 3.

The operational metrics in Table 3 can be further developed and combined with interdependent measures and outcomes across wider services and pathways (for example, ambulance referrals into UCR services and subsequent onward referrals into virtual wards) and can be used as complementary metrics. Existing local data collections and wider collection mechanisms (for example, patient surveys) should also be used to understand the impact of virtual wards.

Table 3: Virtual ward recommended indicators and outcomes

| Categories | Overarching indicators (1) | Improvement area indicators (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational/process metrics | |||

| 1 | Effective governance and clinical leadership | ICS clinical lead at board level. Provider clinical lead at board level. | Staff survey and feedback of working in a virtual ward. CQC well-led rating ICS MDT clinical reference group. Safe and effective out-of-hours provision. |

| 2 | Equity of access | Operating hours (8am-8pm, 7 days a week at a minimum) and out-of-hours provision. ICS wide admission criteria. | Access rates across geography Cost-effectiveness. Patient demographic data (for example, age, ethnicity, gender and deprivation measures) and how patient demographics compare to those of the local community. |

| 3 | Productivity | Occupancy. Accepted and rejected referrals. Balance of step-up to step-down referrals. | Patient throughput. Length of stay Referrals from home/care homes. Referrals from 999/NHS 111/SPoAs/ICC. Referrals from ED and SDEC. Referrals from UCR. Referrals from primary care. |

| 4 | Virtual ward scale and maturity | ‘Beds’ capacity per 100,000 population. Assessment against UEC recovery matrix and other relevant tools/checklists. | Increased workforce productivity. MDT workforce. Patient audits including review of NEWS2 scores and similar tools. |

| Outcome metrics | |||

| 5 | Attendance and admission avoidance (step-up care only) | Emergency admissions and attendances for acute conditions. Emergency readmissions within 30 days of discharge from a virtual ward. | 4-hour ED wait times Ambulance response times. Increased productivity in hospital services. Cost-effectiveness. Patient experience and choice. |

| 6 | Reduction in hospital length of stay (step-down care only) | Admissions from inpatient wards (and not medically optimised for discharge). Hospital bed occupancy reduction for key cohorts. Emergency readmissions within 30 days of discharge from a virtual ward. | Increased productivity in hospital services. 4-hour ED wait time. Cost-effectiveness. Length of stay in a hospital. |

| 7 | High-quality comprehensive assessment, and treatment | Admissions to a virtual ward. Numbers of home visits and video consultations. Numbers of diagnostic tests delivered. Provision of remote monitoring as required by patients. | Provision of comprehensive geriatric assessment. Routine collection of NEWS2, CF and 4AT scores as appropriate. Provision of holistic assessment to identify wider needs including digital literacy and capacity to use remote monitoring equipment. Provision of assessment of an individual’s home environment (for example, falls risk assessment). Health status improvement. Advanced care planning where appropriate. |

| 8 | Improved recovery following period of acute illness or injury | Proportion of older people (65 and over) still at home 91 days after discharge from hospital. New admissions to care homes following treatment on a virtual ward. Referrals to recovery services, VCSE or other community services. | Provision of remote monitoring (and support to use equipment), treatments and interventions . Proportion offered rehabilitation during or following discharge from a virtual ward. Health status improvement. |

| 9 | Positive experience of care at home | Friends and Family Test indicators. Survey and feedback mechanisms for patients and carers. | Carers assessments completed. Provision of assessment of an individual’s home environment, ensuring appropriate safeguarding procedures are in place to protect CYP, vulnerable adults and/or carers. CQC inpatient survey. |

| 10 | Patient safety and protection from avoidable harm | Deaths attributable to problems in healthcare. Severe harm attributable to problems in healthcare or wider concerns (for example, safeguarding). | Incidence of healthcare associated infection and falls in hospital. Patient safety incidents and alerts. |

Notes:

1. Overarching indicators cover the category as broadly as possible and are high-level outcomes/metrics. Some indicators will not be achieved immediately after implementation of a virtual ward; they are more for achievement in the medium to long-term.

2. Improvement area indicators are included to target those groups not covered by the overarching indicators and/or where independent emphasis is merited. These improvement areas include both sub-indicators (for outcomes/metrics already covered by the overarching indicators but meriting independent emphasis) and complementary indicators (extending the coverage of the category).

Appendix 1: virtual wards for children and young people

Virtual wards should be broadened to cover all ages and meet the specific needs of CYP.

Virtual wards for CYP have a positive impact on admissions, bed days and ED/paediatric assessment unit attendance and reattendance (Grout J et al, 2022). Furthermore, for CYP and their parents/carers, virtual wards can avoid the costs associated with attending appointments in secondary care (travel, child care) and need to take time off work and miss time in education.

Virtual wards for CYP are now well-established across England for the treatment of a wide range of conditions including:

- viral-induced wheeze

- asthma

- upper and lower respiratory tract infections

- neonatal jaundice

- bronchiolitis

- infections requiring intravenous antibiotics

- croup

- gastroenteritis

When designing virtual wards for CYP, systems should consider the specific needs of CYP including the safeguarding requirements, early warning systems to spot deterioration in children, technology requirements and the support needs of children’s parents/carer(s).

Appendix 2: virtual wards and supporting carers

Unpaid carers should be recognised as equal partners in care who can provide vital information about the person with care and support needs. To support carers and mitigate any potential risk associated with virtual wards that unpaid carers will be asked to pick up more caring responsibilities, virtual wards must be designed in such a way that enables professionals to:

- identify unpaid carers

- signpost carers to carers’ assessments and further support, such as advocacy and respite care

- involve carers as equal and expert partners in care

- be aware of carer rights under the Care Act and young carer rights under the Children and Families Act. These acts work together so that carers of all ages, and the people they support, can get the assessment and support they need

- have informed discussions with carers about the choices available for care and their right to choose the level of care they provide, including no care if they are unable or unwilling to provide any care

- ensure that carers have access to information about what to do if: they are no longer able to provide care on a virtual ward or their needs or those of the person receiving care increase

The impact on paid carers should also be recognised, including the potential for increasing social care needs for people living in care homes and those with a domiciliary care package. Should any tasks arising from virtual ward care be delegated to non-NHS staff including social care staff, local services should ensure sufficient funding arrangements are in place.

Appendix 3: legal requirements – indemnity

All healthcare professionals have a legal and professional requirement to hold adequate and appropriate clinical negligence indemnity cover, either through their membership of an NHS scheme via their NHS employer or arranged directly.

NHS Resolution has confirmed that NHS care within a virtual ward commissioned to be provided by an NHS organisation will be covered by one of its clinical negligence schemes.

In England most providers of NHS services are covered for clinical negligence risks by one of the state indemnity schemes run by NHS Resolution. NHS services provided by hospital trusts are indemnified under the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST) while NHS services provided by general practice (that is, a GP practice, the main business of which is the provision of NHS primary medical services under a GP contract) are indemnified under the Clinical Negligence Scheme for General Practice (CNSGP). Independent sector providers (social enterprises and independent providers) that are direct members of the CNST are also covered under the CNST where they have been contracted to deliver NHS healthcare services commissioned by an ICS or NHS England as part of cover arrangements. However, not all social enterprises or independent providers are members of CNST – healthcare professionals should check with the organisation concerned if in doubt.

It is important that all clinicians understand what their NHS duties are and operate within the scope of their practice and their employed role. In line with their clinical competence and practice parameters, staff should safely take on higher levels of clinical acuity and complexity that may not have traditionally been part of their roles or delivered in the community.

Appendix 4: further reading and resources

Improvement resources and FutureNHS network

- Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) virtual wards

- Gold Standard Framework for end of life care

- ICS intelligence functions toolkit

- Integrated urgent and emergency care pathway maturity self-assessment

- What Good Looks Like framework

- Virtual Wards Network (on the FutureNHS platform)

National virtual wards guidance

- Access to diagnostics on virtual wards guidance

- A guide to setting up technology-enabled virtual wards

- Pathway-specific guidance for acute respiratory illness virtual wards, frailty virtual wards and heart failure virtual wards

- Supporting clinical leadership in virtual wards – A guide for ICS clinical leaders

- Virtual wards enabled by technology: Guidance on selecting and procuring a technology platform

Safety

- Digital clinical safety strategy

- National Quality Board guidance on safe staffing

- Patient Safety Incident Response Framework and supporting guidance

Pharmacy

- Guidance on pharmacy services and medicines use within virtual wards (including hospital at home)

- The Royal Pharmaceutical Society: Interim professional standards for hospital at home including virtual wards, pharmacy services

Resources produced by voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) partners

- Carers UK Carers’ checklist and advocacy guide

- The British Red Cross’s Virtual inequality? Investigating risk, responsibility and opportunity on virtual wards (also known as Hospital at Home) for health inequalities

Wider community or urgent and emergency (UEC) guidance and frameworks

- Hospital discharge and community support guidance

- Intermediate care framework for rehabilitation, reablement and recovery following hospital discharge

Publication reference: PRN01289